Any day you get to ride a McIntosh-framed motorcycle is a good day.

Terry Stevenson has a good day and shares the experience.

Words: Terry Stevenson Photographs: Steve Parker and Terry Stevenson

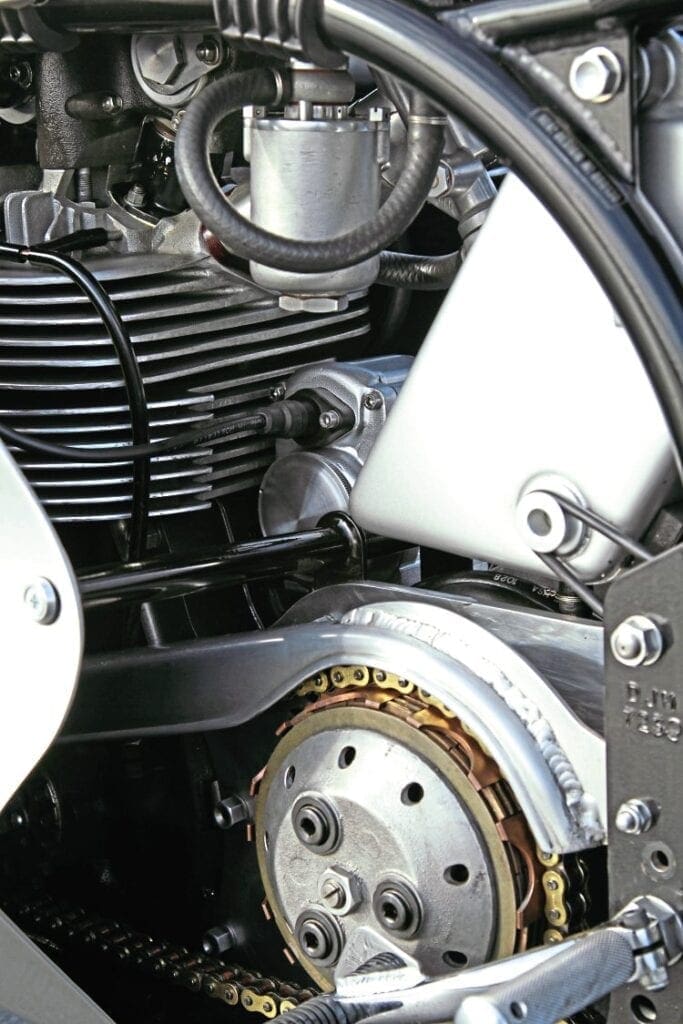

Aucklander Dave Morley is now onto his second immaculate McIntosh Manx Norton 500. His other race bike remains a ‘work in progress’, an ex-Norris Farrow twin shock McIntosh Suzuki GSX1100 F1 machine, which won the Bike of the Show award at a recent Auckland motorcycle show.

Many of the external frame components and engine covers have been machined by Morley in his engineering shop and nothing is spared when it comes down to cost, the example being that all the engine bolts are new, giving just a small indication of the extremely high standard that Morley prepares his machines to. The bike is now 10kg lighter, too!

The ex-Farrow F1 is also his second McIntosh Suzuki, the first being the prized 1982 Bathurst winning machine, now owned by McIntosh employee Pete Welch.

I was looking forward to riding Dave’s McIntosh Norton and I wasn’t disappointed. Playdays, at Hampton Downs, helped out with my test and on the first exit I wondered what the front brakes were up to – well, not much really with a severe wooden feel and a lack of stopping power, so I was more than pleased after a few laps when I got some heat into the drum brakes.

Standard to a 1962 Manx, the front brake is a four leading shoe drum. “Norton only made them the last year they made the Manx Norton’s, in 1962,” Morley says.

Being brought up in the disc brake era I would have ideally liked more braking power early on, however Morley explained that if he set the front brake lever to be out where I wanted it the lever would then “move out” when they heated up. It served to remind me that I had to remove my modern ‘hat’ and get my head into the period of the machine.

Barrelling along the front straight I checked out the massive amount of legroom a rider has on a McIntosh Manx, at 5ft 11in and with long arms I almost had difficulty reaching the back of the seat tailpiece – it’s so far back! It is a feature I decided would be handy to get down behind the screen once I picked up some speed and for slipstreaming in a race.

However, Dave says he’d like to see the quite low fairing blade to be a fraction higher, and I came to the same conclusion. With my helmet on the tank I couldn’t see forward very clearly due to the near horizontal ripples in the perspex, but also I don’t think my helmet was all that much out of the slipstream.

The weight distribution made it feel like much of the McIntosh Manx Norton’s weight was at the front.

As such it has fairly front heavy – and therefore slow – steering, and as a result I wasn’t sure where the best riding position was.

If I put all my weight right up front I was concerned about unweighting the rear wheel too much that might cause it to slide, which turned out to be the case on two occasions.

On my third exit I began experimenting with my body position to see what worked best for me. With limited time to experiment while taking in the machine’s capabilities and learning to ride it faster each time I went out, on corner entry I found it best if I kept my weight slightly back to get the best steering and braking combination.

It surely wasn’t right back on the elongated seat; although on the faster corners Morley said he moves his weight rearward mid-turn to control any rear end slippage. More time on the bike would sort this out.

With only three exits I spent most of my time trying to get my corner speed up to make best use of the motorcycle for a fast lap, which Morley says is the secret of riding the McIntosh Manx Norton.

“You don’t have huge horsepower so you really need to stay off the brakes, so corner speed is everything,” Morley explained. And Morley knows what he’s talking about as he raced for Syd Lawton (an early 1950s works Norton rider).

With team-mate Peter Bugden, Morley was third in the 1958 Thruxton 500 on a BSA Gold Star, as a teenager. “I rode a 350 Manx Norton for him and a Matchless G45 from 1958 to 1961,” he said.

Unfortunately, national service in the British Army pretty much ended his burgeoning race career. “I still rode bikes but it was difficult,” Morley said. Dave then emigrated from the Portsmouth area in the UK to New Zealand in 1965.

His McIntosh Manx Norton is an absolute stunner, and it goes as good as it looks. “I think you put your own little mark on it, it’s mostly cosmetic and although it looks very trick, in essence it probably doesn’t make you go any quicker. But it fools a lot of other people and they think ‘wow, what a trick looking bike’.”

This special Manx has many minor parts in aluminium rather than steel, and while parts of the forks look chromed, they are chromed aluminium, all saving a few important kilos in weight.

“It has the highest spec Summerfield engine that you can get with a plain bearing crank. It has a 92mm bore and a short stroke so it’ll rev very cleanly to 9500rpm, but it makes good power at around 8000.”

Morley’s McIntosh has a self-set redline at 8200rpm which, in respect to the engine and the owner I never went over, and I didn’t really want or need to go over about eight grand since it is such a high revving big single that I was still getting used to.

The power delivery of 60 rear wheel horsepower is tremendous! I could deliberately pull out of a corner in too high a gear from 3000rpm and it would pull without too much fuss.

Sure, it made more sense to be over about 5000 and in the right gear for a fast lap, but I am a tester and this is what I do, all the same I’d like to know what the torque output is.

One could argue it didn’t really matter what revs the powerplant was spinning at on corner exit, however my opinion is it seemed to make a little more power around 7000rpm.

Good luck to whoever wins that discussion, but it does have a very linear power curve that peaks out around the 8000 mark.

The engine is fed by an Amal carburettor that Morley bored out to 40mm, from 38mm. The motor runs on methanol, and is nudging a 12.8:1 compression ratio.

“You can’t get any bigger because two things fight you – the size of the valves, we have an almost 2in inlet valve, and we have high lift cams with pocketed pistons. So you’ve got everything going against you for racing compression.”

Its six speed transmission helped matters, although with the motor driving like a large capacity road bike engine five speeds wouldn’t add too much to your lap time.

Each time I rode it I felt more confident and went faster. It was both a pleasure and an honour to ride Morley’s immaculate McIntosh Manx Norton 500, and I’d ride it again in a flash.

McIntosh Suzuki GSX1100–A Power of Good

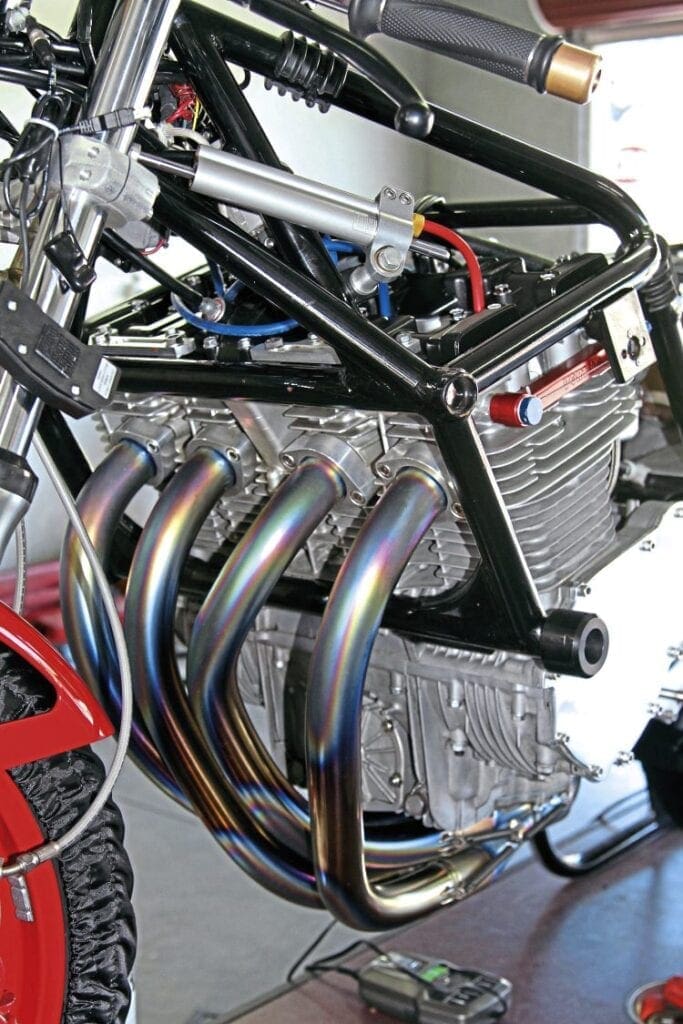

Of all the McIntosh Suzukis built the most treasured is the 1982 Bathurst winning machine on which the late Rodger Freeth famously won the Arai 500 endurance race.

The Australians were stunned by the Kiwi victory on an unknown bike using a home-made chassis – by two laps, and it lead directly to a fruitful business for Ken McIntosh making ‘Bathurst Replica’ McIntosh road kits, and race bikes.

Completed in December 1981, this machine was the first McIntosh with a GSX1100 engine after the initial two McIntosh Suzukis were fitted with GS1000 powerplants.

Dave Morley purchased the 1982 Bathurst winning McIntosh Suzuki GSX1100 in 1999 off Pete Mathieson, who was the second owner after buying it off Freeth in the early 1980s. It remains one of the most immaculate motorcycles found anywhere within NZ.

My track test was the second time I had ridden this iconic race bike, with my first ride during the late 1980s when it was in a well-worn state. Riding it for a second time around Pukekohe’s ultra-fast racetrack was an experience to behold and a credit to Morley for rebuilding it to such a high standard.

Out on the track the 1173cc engine would freely rev out and I found I was having so much fun on the bike that I seldom let it drop below 8000rpm.

Although it had reasonable mid-range pull, most power came in between 8000 and 9500, which tied in well with its special close ratio gearbox.

Using a reverse shift pattern I was selecting top gear just on the kink of the old back straight and letting it drive through right to the end of the straight, approaching around 270kmh.

I didn’t need to take it above the 10500rpm redline as I found the power began tapering off after 9500, so 10 grand was my own limit for this historic ride.

In the pit lane I found the engine didn’t really want to live much below 3000 so I had to keep the revs up to avoid stalling due to its high 13:1 compression ratio. Internals include Yoshimura pistons and stage one cams, fed by 33mm Mikuni smoothbores.

Freeth used its mid-range power to good effect on corner exit against the RG500s and TZ750s around NZ’s tight racetracks and street circuits.

Yoshimura produced a limited batch of 10 special close ratio gearboxes at the time for world distribution, with one set going into this McIntosh.

Gone with the original gearbox is the wide gap between first and second and out on track the highly geared Yoshi transmission made a huge difference around Pukekohe, although the transmission’s best features are the five close ratios and the smooth, positive gear changes.

Riding the McIntosh fast gives a raw, direct and rugged feel as there is no cush drive in the McIntosh-produced rear hub. With such an odd, tight feeling from the overall package, every rider input was easily measured and controlled, which turned into excellent feedback through the tyres.

To maintain its original state after a complete refurbish, the original 18in wheels were retained, running Avon tyres. Getting power to the ground was the big issue for large race bikes back then when 18in wheels and relatively narrow tyres were as good as they got at the time.

Being such a low bike it was super-easy to change direction and I can understand why the McIntoshes were so successful. We measured the wheelbase at 1450mm, which was around 100mm less than the big production bikes of the day, so it’s little wonder it was easy to corner in 1982.

The heavily triangulated frame uses the engine as a stressed member and it felt rock-solid. There was no trace of frame flex so it tracked straight and true and went exactly where I wanted it to go.

I found the steering was really good in the high speed corners – nice and stable when flicking it from side to side. It was all very easy until I arrived at the slower turns, where the slightly worn but shallow profile front tyre resisted handlebar pressure to lean the machine over, possibly also due to a relatively shallow steering angle.

If you want to ride something like this fast, you have to be super smooth in everything from gear changes, clutching, braking and cornering. The McIntosh was no exception.

The rear shocks felt good on the really bumpy track but up front I experienced a little front-end patter heading into turn one.

The front brakes were excellent and as warned, entering turn one the pads were already pushed away from the Lockheed twin calipers, just as they did over 30 years ago – thanks to the non-floating Brembo front discs and a super-bumpy front straight. After each full circuit I had to give the lever a trial nudge to bring the pads to disc before needing the brakes for real.

The handlebars are in an ideal position for the bike of that period, when straight arms were king. Like all race bikes back then, the foot pegs are high-set compared to the seat position, which cramped my legs and prevented all but the smallest of rider body language in the turns.

On the bike my knees were pushed out the side of the tank and fairing, which placed them out in the slipstream, so it came as a surprise when Ken told me he made the curved tank just to look good, not to fit a rider’s knees. Still, what could anyone possibly do to accommodate Freeth’s (also known as Super Frog) lanky 6ft 2in frame?

Tucking in behind the low front fairing was a bit of a mission that still left half of my helmet in the slipstream collecting wind.

McIntosh based his stylish seat unit on a Kawasaki racer, with the first few bikes, including our test machine, incorporating a slight forward overhang at the top of the seat area.

He ditched the cool-looking but impracticable ledge when they realised it dug into the small of the rider’s back when they sat up, and all remaining seats thereafter had a sensible vertical back.

The seat was low enough I could place both feet flat on the ground, so the riding position of the McIntosh was considerably lower than its closest rivals of the period, the Steve Roberts-built ‘Aluminium Monocoque’ (1982) and ‘Plastic Fantastic’ (1983), which I’ve also tested.

McIntosh-framed race bikes carved a successful path spanning several years during the early 1980s in the hands of a number of top New Zealand riders including Freeth, Dave Hiscock, Bob Toomey, Robert Holden and Norris Farrow.

Overall, Ken McIntosh did an outstanding job. Ken was around 26 years old when he built the 1982 Bathurst winning McIntosh Suzuki and even today there wouldn’t be many people of that age in the world with a similar level of proven race-winning engineering ability.

The future of this rare McIntosh is assured under the ownership of Pete Welch, Ken’s long-time staff member, who helped build it all those years ago. Bravo!

Read more News and Features online at www.classicracer.com and in the latest issue of Classic Racer – on sale