Words: Bruce Cox Photographs: Randy Hall Collection

In the early 1970s, 500cc Grand Prix racing was boring in the extreme, usually consisting of a cruise to the chequered flag by Giacomo Agostini and the MV Agusta ahead of a field of outdated British singles.

Small wonder, then, that to most fans in that era Formula 750 was road racing’s premier category.

Especially so in its earliest years before Yamaha interpreted the rule book down to the letter and built enough four-cylinder TZ700/750 two-stroke racers to satisfy the 200-unit homologation rule. This was a smart but cynical move that, to all intents and purposes, turned F750 into little more than a ‘one-make’ series from 1975 onwards.

Prior to that the F750 manufacturers, who enthusiastically embraced the initial American-inspired concept, had followed the AMA Class C rules which dictated that it was to be a formula that had to be based on production motorcycle engines.

In those early years there was a wonderful mix of competing brands. BSA, Triumph, Norton, Honda, Ducati, Harley-Davidson and even MV Agusta four-strokes competing against two-strokes ranging from the giant-killing 350cc Yamaha twins to the fearsome 750cc triples from both Suzuki and Kawasaki – all of which had two-stroke engines that were at least based on their road machines.

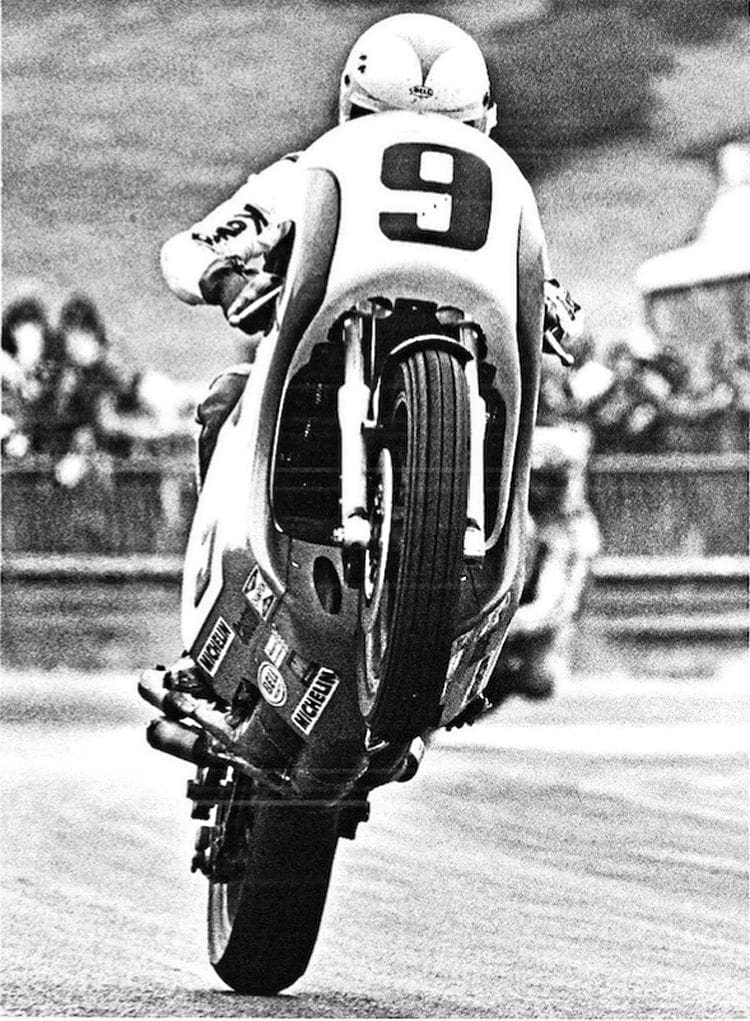

Arguably the most successful – and certainly the most eye-catching–of the two-stroke teams in those pre-TZ750 days was Kawasaki with its distinctive lime green racers that were inevitably and immediately christened ‘the green meanies’.

These had been carefully developed from 1971 onwards by a young Californian by the name of Randy Hall, who at first alternated between team management and development engineering roles before essentially combining both roles from 1973 until the end of the F750 era in 1976.

He then continued to enjoy a long career with Kawasaki for a dozen more years or so, including working in both research and development areas as well as a stint as the Superbike team manager between 1979 and 1982.

During the winter of 1967/68, Rod Gould and I were living in California and became friendly with Randy (writes Bruce Cox). And while he was still young (in his mid-twenties) and single, he decided to give up his job working for a manufacturer of electrical switchgear and motor control units and come back with us to see what Europe had to offer.

Throughout the 1968 season, he engineered Rod’s bikes on the British short circuits and the GP trail and did that so well that Rod was able to finish fourth on his Yamaha-Bultaco in the 250cc World Championship as the leading privateer behind Phil Read and Bill Ivy on the factory Yamaha V-fours and Heinz Rosner on the MZ rotary-valve twin.

Randy came back for more in 1969, which was the season in which Rod totally dominated UK short circuit racing with his 250 and 350 Yamahas and finished fourth and fifth in those World Championship classes. And in 1970 it all came together as Rod took the World 250cc Championship with Randy very much a key figure in that achievement.

This was the pinnacle of Randy’s achievements in Europe but there was much more to come back home in the USA.

He had married in 1970 and therefore had decided to return to California for 1971, having achieved his ambition of helping Rod to the Championship. And with a World Championship on his CV, it was only a matter of weeks before Randy had been hired as the first race team manager for Kawasaki Motors Corporation USA.

Taking up the Challenge

It was a big project as, starting from the proverbial clean sheet of paper, he had just over two months to get everything up and running and get Ralph White and Yvon Duhamel on to the grid for the Daytona 200 with factory-prepared 500cc H1-R triples for the opening race of the American Motorcycle Association’s Grand National Championship season.

Randy, however, did have some knowledge of the H1-R as he had watched New Zealander, Ginger Molloy, race one to second place in the 1970 500cc World Championship behind Giacomo Agostini and his MV. Early in that season Ginger had entered the Daytona 200 and, even with two refuelling stops for the thirsty triple, had finished in seventh position to earn a nice bit of prize money to help him through his GP year.

During the Daytona qualifying Ginger’s H1-R was electronically timed on the high-speed oval at 159.83mph, so Randy was certain that his new bikes would have the speed to do the job.

Otherwise, the pressure was on. In ten short weeks Randy had to hire mechanics, set up a separate race shop, plan and schedule for the US season and provide technical assistance for the private riders who had chosen the new Kawasaki triples as their race bikes for the year.

The 1971 version of the 500cc three-cylinder racer was now called the H1-RA model, reflecting numerous improvements to the engine, although the chassis was basically the same as the 1970 version.

The main change was a new Kokusan self-generating magneto type CDI electronic ignition that replaced the old battery and contact breaker system.

New cylinder castings with different port timing and new specification exhaust expansion chambers raised the peak horsepower rating of the engine to 80 horsepower at 9500rpm.

Aiming for more durability, the big end connecting rod bearing was changed to single caged rollers rather than the paired rollers of the 1970 motor.

An 1100sq ft industrial unit was leased in Santa Ana, California, and Randy hired Harold Sellers and Steve Whitlock as race mechanics – two spanner-men well-known to him from his earlier days on the California racing scene.

The team riders would be Californian Ralph White, winner of the 1963 Daytona 200 for Harley Davidson, and Yvon Duhamel, a French-Canadian rider who had been riding for Yamaha Canada. He had proved his winning potential with second and fourth places at Daytona on a 350cc Yamaha in 1968 and 1970, as well as two 250cc class wins there in 1968 and 1969.

These riders would race special H1-RA ‘S versions’ – development machines built by the factory in Japan and with further performance and reliability improvements being made by the R&D department over the course of the season.

Randy also began to develop the bikes in the light of what he had learned during his time with Rod Gould and Yamaha in Europe.

He obtained clip-on bars and Ceriani front brakes from Italy and Girling shock absorbers from England plus some Swedish-made adjustable steering dampers – the latter a welcome fitting for the riders as the peaky power characteristics of the triple meant that it did have a tendency to shake its head more than a little when the power came in!

Randy was also able to put his European contacts to good use as he had become friendly over there with Dave Simmonds, who had won the 125cc World Championship for Kawasaki in 1969 – the first world title for the marque.

“Dave gave me some good input on springs and damping characteristics and other things that he did to improve the handling and performance on the H1-R that he had raced in 1970,” recalls Randy.

“But there was much more for us to do before Daytona than fit parts and play with springs and settings,” Randy continues.

“This included aerodynamics and although there was no problem with the fairings I thought that the little round tail section of the seat was not contributing anything to top speed.

“This feeling was based on the fact that Jerry Branch, another friend of mine from the Sixties’ California racing scene, had done an extensive evaluation in the Cal Tech wind tunnel for the streamlining package that had added almost 10mph to the Daytona qualifying speed of Harley Davidson’s side valve V-twins.

“It had raised their lap speed average around the banked oval from 140.82mph in 1967 to 149.08 in 1968.

“According to Jerry, one of the big improvements was the design of the seat that improved the airflow off the back of the rider and the motorcycle. So I made a drawing of a longer, wider and taller seat with a sloping shape using Jerry’s results, but added a small raised lip at the back that aerodynamically made the airflow act like the seat was much longer than it was, thus giving a larger increase in stability and a further lowering of the drag factor.

“We got the finished seats just before the truck left for Daytona, so we ended up mounting them at the speedway. This actually gave us good test data, as we were able to evaluate the original round seat against the new seat where it really mattered – on the track.

“The riders agreed that the stability was improved with the new seat and that the bike actually picked up rpm while at maximum speed on the oval. The new design had proved to be a positive step and achieved both of the aims that I had hoped it would, so much so that it became the standard seat on Kawasaki road racers for many years.”

So far so good but there had been even more hustle going on pre-Daytona that did not focus on the bike itself. Initial rider experiences in 1970 had indicated that fast refuelling stops were going to play a part in Kawasaki racing strategy as the H1-R was a thirsty beast.

And that wasn’t just a problem in the Daytona 200. Other AMA Nationals were 125 miles long, which meant that the 750cc four-strokes, and even the Yamaha 350cc two-strokes, could go through non-stop on the six gallons of fuel tankage allowed.

Not so the Kawasaki… the triples may well have been the fastest bikes out there but they gobbled up the gas at a rate that meant a refuelling stop at every race was inevitable.

So, with his development engineer hat on rather than that of team manager, Randy set to and designed the first-ever fast-fuelling system for motorcycle racing to replace the ‘dump cans’ (really just a funnel with a huge mouth) that had been the norm up until then.

Randy’s system employed the now familiar high level fuel container, in this case a 35-gallon drum on a 10-feet tall stand. From this ran a big-bore (three-inch diameter) hose with aircraft-type connector that quickly locked on to (and off again from) a special large one-way valve on the side of the motorcycle’s tank.

In fact, there was one on each side of the tank as the pits were on different sides at different tracks on the AMA Championship trail and some circuits ran clockwise while others were run counter-clockwise.

On the bottom of the drum a ‘dead man’ valve was installed that had to be held open during refuelling. Releasing the valve automatically shut off the fuel flow if a problem was experienced with the system during race refuelling.

The system could put five gallons of gas into the tank in about five seconds – and when you put that much gas into the fuel tank that fast you need to get the air out quickly. Randy’s system, therefore, mounted a 1-1/4” dry-break fitting on the top front of the tank, to which was attached a hose with a catch bottle on the end of it so as not to allow overflow gas on to the pit area track surface.

Finally, special cellular fuel cell foam was installed inside each tank to help the incoming fuel to disperse and fill the tank evenly. The fuel cell foam also kept the fuel inside the tank from sloshing from side to side as the rider changed direction on track, thus helping greatly with the handling and stability.

Getting the system designed and built in time for Daytona was a challenge but one which was helped by the fact that Southern California is one of the hot spots of the performance motorsports industry and Randy already knew many of the key people involved, notably guys like motor racing legend, Dan Gurney, whose All-American Racers operation was just down the street from the Kawasaki race shop.

He and Randy, along with the rest of the staff from the respective race shops, often used to lunch together, or meet for an after-hours beer at one or other of the facilities. And with Dan always being a keen motorcyclist, he was always ready to help out… even to the extent of donating some fuel system parts that he no longer needed for his Indianapolis 500 racecars.

Six people other than the rider were involved in the refuelling operation. Hefty Steve Whitlock got his weight behind a six-foot tall board that the rider planted his front wheel into when he came screeching into the pit; Randy operated the fuel delivery while Bob Hansen took care of the air bleed system and Randy’s brother, Kenny, stood ready to activate the emergency shut-off valve if necessary.

While all that was going on, Harold Sellers checked the rear tyre and adjusted the chain and then, with the help of a third mechanic, Hurley Wilvert, pushed the bike back out into the fray. After much practice, the squad developed the refuelling operation into one worthy of a NASCAR car race team.

Finally, despite the frantic pace of pre-Daytona activity, Randy also found time to specify and commission some frame modifications.

These were based on the input from Ralph’s testing at Riverside Raceway, where he found that the H1-RAS as delivered from Japan didn’t change direction easily when going through that track’s series of fast and flowing right- and left-hand turns.

Ralph felt the bike’s high centre of gravity was the primary cause of this so the lower frame tubes of the main engine cradle were cut out and then repositioned to drop the engine an inch lower to the ground.

Ralph tested and liked the modified chassis and did not find any ground clearance problems or other negatives. Therefore, Yvon Duhamel’s bike was modified in the same way.

With this amazing amount of work having gone on in the mere ten weeks before Daytona, it would be nice to report that the efforts of the dedicated Kawasaki squad were rewarded with a happy ending. But that fairytale didn’t come true.

Daytona debut

The race at least started well, with Yvon leading on the first lap and mixed up with the other factory teams all battling for the lead in the early stages. Later on, however, he crashed in the infield horseshoe turn and was out of the race.

But at least he had the satisfaction of proving to himself and the team that the bike was a contender. Poor Ralph White, on the other hand, was in and out of the pits with different issues all race long and never in contention for even a respectable finish.

Things could only get better after that and thankfully they did. Ralph got a third at Road Atlanta and Yvon was fourth on the tight track at Loudon in New Hampshire – fittingly the closest US track to his home across the border in Quebec.

Two races later Yvon improved that to a third place on the faster track at Pocono in Pennsylvania and then came the payday that the team so richly deserved.

In the 200 Miles race on the Daytona-style banked track at Talladega in Alabama, Yvon was able to claim Kawasaki’s first AMA National Championship win. And the icing on that much-enjoyed cake was the fact that Ralph White was fourth, just behind the factory BSA triples of Dick Mann and Don Emde.

This was further added to by the fact that Mike Lane and Bob Wakefield finished 1-2 on their Kawasakis in the Junior race, ahead of a feisty little dirt-tracker dipping his toes in road racing waters and going by the name of Kenny Roberts!

For 1972, Kawasaki USA decided that it needed Randy’s special talents as a development engineer in more than just the racing end of things and switched him from the racing department to become its first multi-cylinder model development engineer. This was an important role indeed as it involved the development and quality assessments of a whole range of new models.

Not just the new three-cylinder two-strokes that were to be launched in the 750cc, 250cc and 400cc classes alongside the 500cc H1 but also a new and secret four-cylinder, double overhead-camshaft four-stroke that was arguably the most significant model that Kawasaki has ever made.

This was the 900cc Z1 – the bike that changed Kawasaki’s whole direction as far as production road-going motorcycles were concerned.

To enable Randy to concentrate upon his development role, Kawasaki farmed out the day-to-day running of the race team to the experienced Bob Hansen who had been in a similar position with Honda and who had overseen Dick Mann’s 1970 Daytona 200 victory with the CBR750.

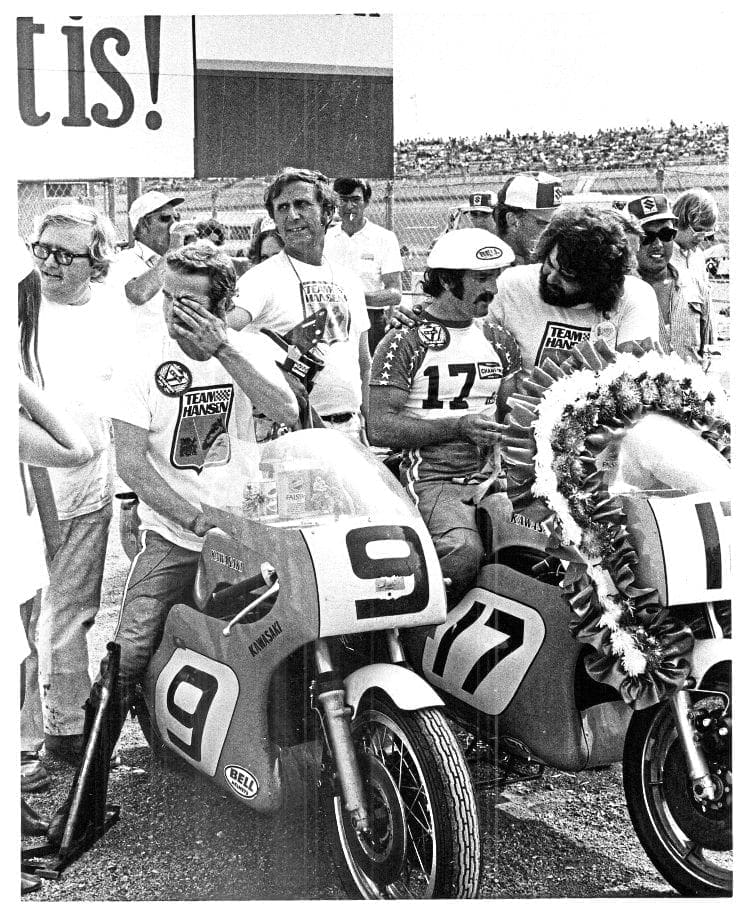

So while Team Hansen Kawasaki got on with the business of going racing, Randy was entrusted with the engineering and development of the new bikes provided to it. And very effective bikes they were, being the new 750cc H2-R versions of the original three-cylinder two-stroke.

Team Hansen Kawasaki won three AMA National road races that season with riders Yvon Duhamel (who won at Road Atlanta and again at Talladega with Gary Nixon second) and Englishman, Paul Smart, who won the big-money end of season race at Ontario Motor Speedway in California.

Finally, as if his dual role of development engineer on both road and race bikes was not enough, Randy also worked as the link between Kawasaki and Elliot Morris in the development and testing of the first volume production cast magnesium alloy motorcycle wheels for racing and, in later years, aluminium road-going wheels for Kawasaki models.

He had prompted Kawasaki’s interest in cast wheels after his GP years in Europe, where he had seen those created by Peter Williams for his Matchless G50 and the JPS Norton.

With much of his development work fulfilled during 1972, Randy became Kawasaki’s road racing manager again in 1973 when the administration of the race team was taken back ‘in house’.

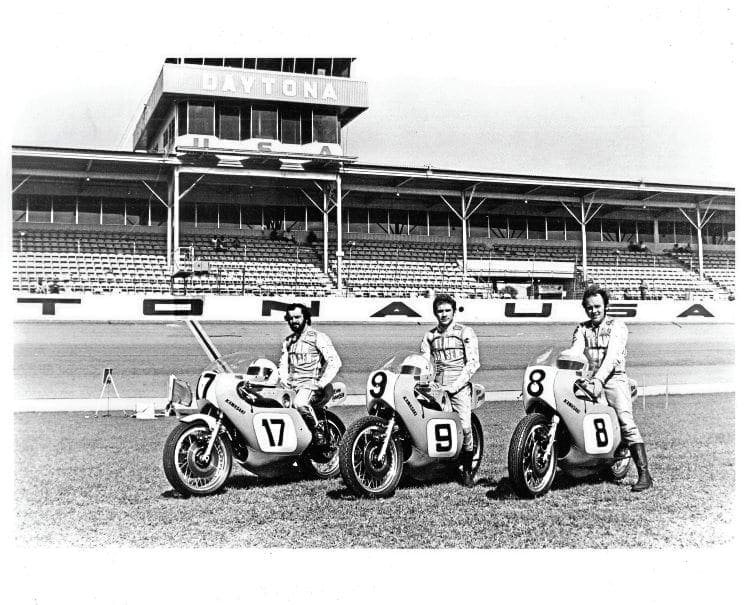

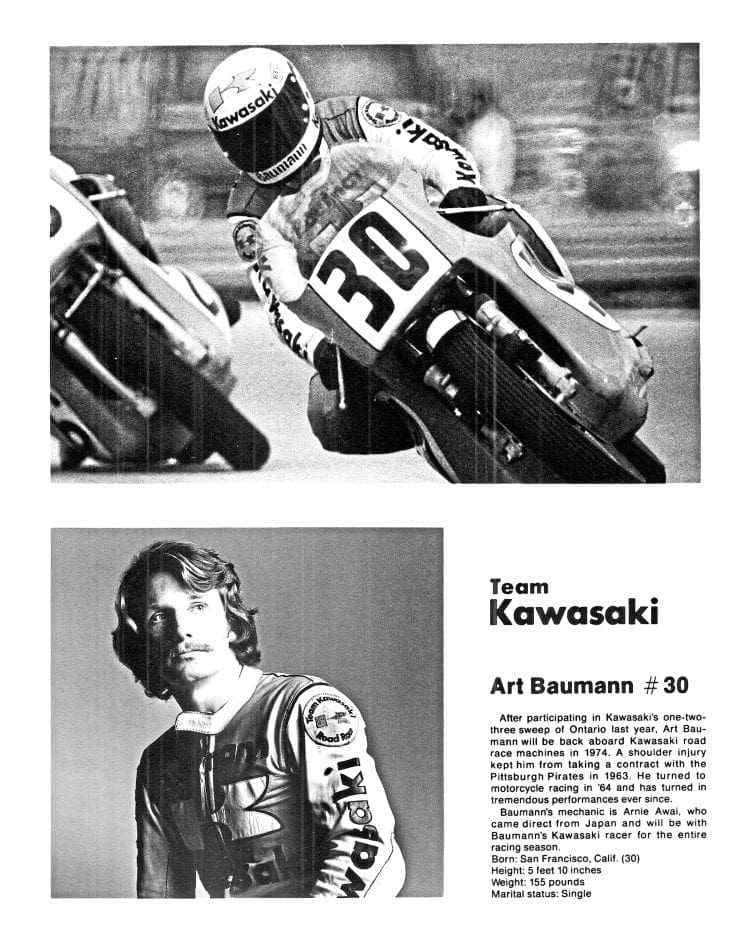

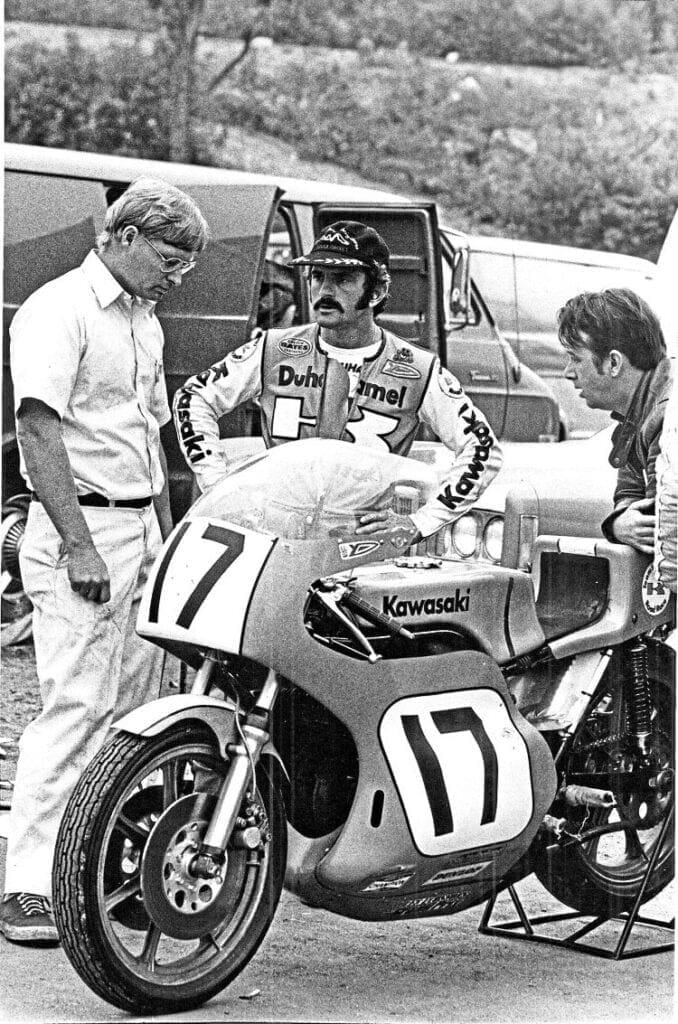

That year saw an expanded Kawasaki effort in the American Grand National Championship series with three actual team riders, these being Yvon Duhamel, Art Baumann and Hurley Wilvert (promoted from his mechanic role) as well as Gary Nixon and Englishman Cliff Carr on official ‘satellite’ teams with their factory bikes prepared by their own highly skilled engineers, Erv Kanemoto and Kevin Cameron.

One of the major things that changed for 1973 was that the AMA, as a member of the Federation International Motocycliste, agreed to follow the FIM rules for the new Formula 750 World Championship series. The Daytona 200 race would be the first race of the year run under these regulations.

Meeting these new rules created a huge new development problem for the Kawasaki factory as AMA rules allowed the homologation of special cylinder castings used on racing versions of road models.

All of the previous three-cylinder race engines that Kawasaki had designed and built used special ‘racing only’ cast cylinders that had been approved by the AMA. The FIM F750 rules, however, required stock crankcases, cylinders and cylinder heads.

This made major problems for Kawasaki because the routing of the exhaust expansion chambers, along with frame design and fairing requirements, meant that the two outside cylinder castings for the racing engines had the exhaust pipe connections angled inwards towards the centreline of the frame.

The production cylinders on the road-going models, however, angled the exhaust port connections outwards.

The only thing Kawasaki could do was to switch the outside cylinders to the opposite side of the engine. This solved the exhaust port connection problem, but to do this they had to cut off the outside fins of the cylinder castings.

Now all three cylinders only had limited cooling fins on the front and back of the cylinder and none at all on the sides.

This lack of fins certainly didn’t help the air-cooling of the engine and piston seizure problems became a critical tuning issue through the year.

Even so, Team Kawasaki won five of the nine road races that season (two wins for Yvon Duhamel and three for Gary Nixon) making it the most successful squad on the American tracks – and Gary added the cream on the cake by being the most successful road racer in the American Grand National Championship series that still mixed dirt and tarmac events.

In 1974, however, it was a different story as it was the year that Yamaha’s 700cc four-cylinder racer made its dramatic racing debut with a Daytona 200 win for none other than Italian superstar Giacomo Agostini, who had seen the two-stroke writing on the wall and defected from MV Agusta.

Both Cliff Carr and Gary Nixon had also defected to a different team for 1974 – from Kawasaki to Suzuki – so the Kawasaki team continued under Randy’s management with the same three directly contracted riders as 1973, those being Yvon Duhamel, Art Baumann and Hurley Wilvert.

But this little squad was essentially on a hiding to nothing against a rampaging horde of Yamaha riders on the ‘out and out racer’ water-cooled fours.

As well as the Yamaha US team of Kenny Roberts, Gene Romero and Don Castro, there was also Steve Baker on the Yamaha Canada bike and dozens of America’s top privateers who had chosen the TZ700/750.

On top of that, the Yamaha factory team had peppered the pot still further by bringing its World Championship riders, Agostini and Teuvo ‘Tepi’ Lansivuori over for the big money season-opener at Daytona.

Despite this, Kawasaki’s best result of 1974 was Hurley Wilvert’s third place finish at Daytona behind Agostini and Kenny Roberts but ahead of Castro, Lansivuori, Romero and Ken Aroaka on a Yamaha Japan entry.

Essentially, however, not only were the Kawasakis out-sped by the water-cooled Yamaha racers but they were also forced to run at a pace which pushed their production-based air-cooled motors beyond the bounds of their capabilities. Both Yvon Duhamel and Art Baumann were early retirements at Daytona.

New models

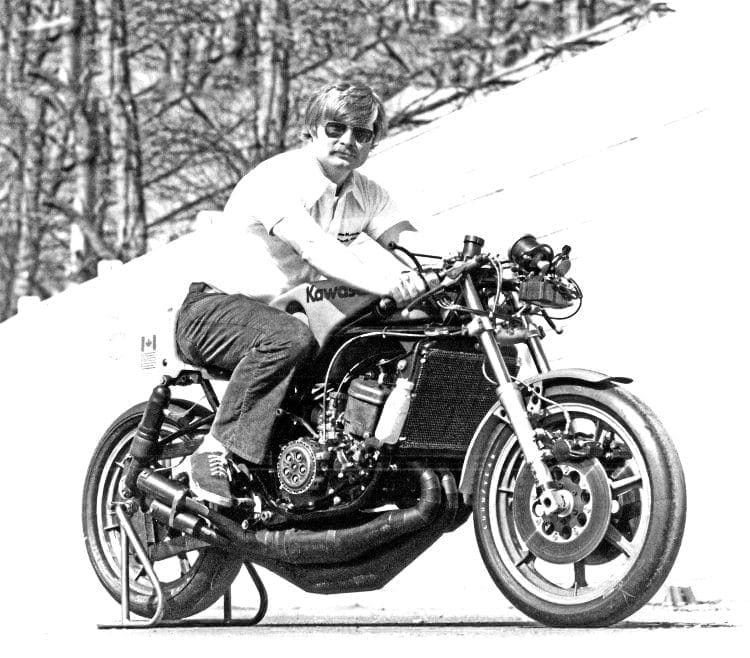

In the light of this, the 1974 season was one of regrouping and Randy spent much of his time liaising with the Kawasaki factory in Japan on the design and development of a new water-cooled three-cylinder KR750 road race model that would hopefully level the F750 playing field with Yamaha, and the new KR250 racer with twin in-line cylinders and a seven-speed gearbox that would challenge the established machinery from Yamaha and Harley-Davidson (aka Aermacchi) in that class of World Championship racing.

Kawasaki had been working non-stop on the development of the new bikes through 1974 and in October that year it was helped by the fact that the FIM, followed by the AMA, made a major change in the homologation rule by dropping the number of motorcycles needing to be built for qualification from 200 down to 25.

This change took a lot of the pressure off having to build 200 hand-built racing motorcycles for homologation.

The only similarity between the 750cc H2-RAS and the new KR750 was that they were both 750cc three-cylinder piston port two-stroke engines with the primary drive on the right-hand side.

Among the myriad differences, the most obvious ones were that the KR750 had a six-speed gearbox, instead of the older bike’s five, and the dry clutch had two more clutch discs. A water pump was built into the magnesium right-hand clutch cover as part of the change to water cooling.

Unfortunately, there had not been time for enough of the track testing of these two new models that was needed to fully develop their reliability and performance. This meant that the racing season would have to also serve as a development year in full view of the public and the press. It was a gutsy decision by Kawasaki to go ahead on this basis but it also showed how committed the factory was to make these new KR models – and, furthermore, to make them winners.

The faithful Yvon Duhamel would lead the Kawasaki US team for 1975 and Gary Nixon had returned from Suzuki, bringing his ace tuner, Erv Kanemoto with him.

They would be joined by a promising American youngster, Jim Evans, who had first come to the attention of race fans by finishing third on a privately entered Yamaha TZ350 in the 1973 Daytona 200 behind the factory bikes of Jarno Saarinen and Kel Carruthers.

Sadly, Jim’s career with Kawasaki was over almost before it had really begun. He suffered head injuries in two heavy crashes that forced him into a far too early retirement from racing.

Yamaha continued to dominate in both the American and World Championship events and Kawasaki’s one bright spot of the 1975 season didn’t come along until September when Yvon Duhamel won Kawasaki’s first FIM Formula 750 Championship race at the famous Assen Grand Prix circuit in the Netherlands.

Another bright spot for Randy in 1975 was a win by Mick Grant at the Isle of Man TT. Not because he had any involvement in it but because it saw a prediction come true that he had made during a factory race development meeting in Japan at the end of 1973.

Asked for his opinion on the potential of the revised 500cc H1-RW triple, Randy had replied that he did not think that it would ever be a contender for a World Championship title but that it could very well be an Isle of Man TT winner in the hands of a Mountain Circuit specialist like Mick Grant.

Two years after that prediction, Mick did win the 500cc Senior TT race on a 500cc H1-RW. Later that week, on a KR750, he retired in what was then called the Classic TT – but not before he set a new Isle of Man outright lap record of 109.82mph. Both efforts mightily pleased Randy Hall when he heard the news on the other side of the world.

By 1976 the Kawasaki USA road race team had been scaled way back with just Yvon Duhamel riding directly for Randy and with Gary Nixon coming back again with Erv Kanemoto and aiming to compete on a KR750 in both the American road races and the FIM Formula 750 World Championship.

It was a good year in many ways for Gary but also an intensely frustrating one in that he finished second in the two things that mattered most to him – the Daytona 200 and the FIM F750 world title standings.

His second place Daytona ride was his best placing there since he had won it on a Triumph 500cc twin in 1967 and the best result ever for a Kawasaki two-stroke triple in what was America’s most famous race back then.

Sadly, Gary died of complications following a heart attack at the age of 70 in 2011 and the manner in which he was denied the 1976 World F750 Championship (then actually known as the FIM Formula 750 Prize) was something that he was bitter about to his dying day.

The confusing results of the FIM Formula 750 race in Venezuela caused the championship’s final standings to be shrouded in controversy. Nixon appeared to have won the Venezuelan race, but the race organisers originally credited Yamaha’s Steve Baker with the victory, even though he had lost a lap in the pits. Official protests by Nixon, and other riders about their finishing positions, caused the Venezuelan organisers to later change the results declaring Nixon as the winner.

All these official protests to the FIM over the results at the Venezuelan race resulted in a decision that the whole event had been so mismanaged that the FIM threw it completely out of the season points reckoning. As a result, Gary could not even lodge an appeal.

There would be no points for Gary, or anyone else, from that round. If Nixon had been awarded the Venezuelan victory, then Nixon and Kawasaki would have won the FIM Formula 750 world championship by one point over Spaniard Victor Palomo.

It was a dismal way for Kawasaki’s California-based team of ‘green meanies’ to depart the scene – and depart they did as it was decided to discontinue the road racing effort and concentrate on motocross from 1977 onwards. The team, which had the motorcycling public’s pulses racing for six memorable years, eventually faded away without the final championship it deserved.

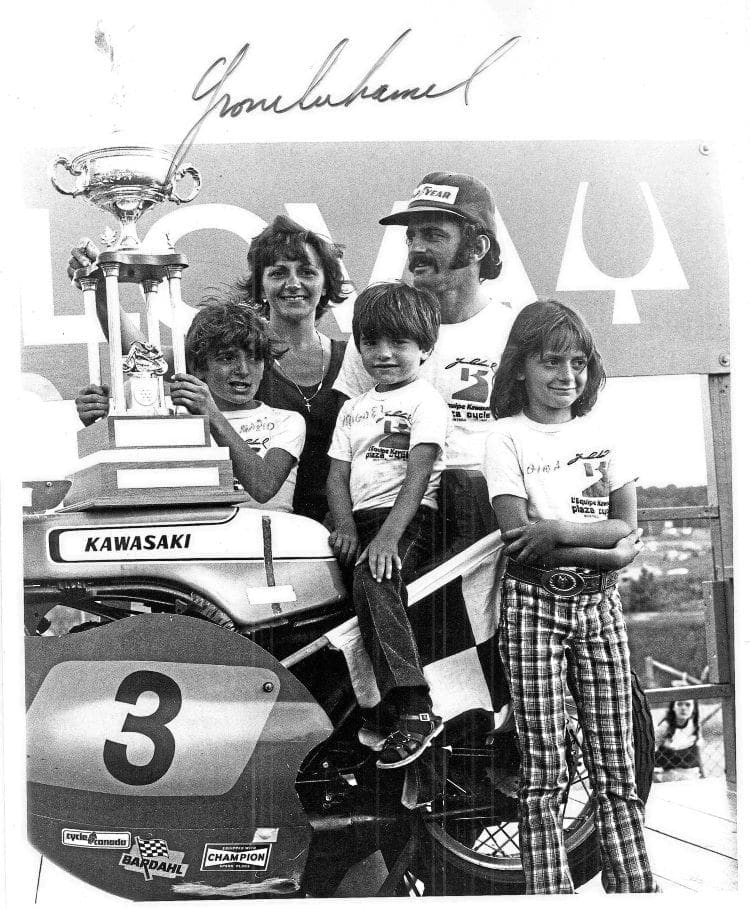

Randy Hall went back to the Research and Development Center, but at least there were still a couple of races to run with Yvon Duhamel under the auspices of Kawasaki Canada and very much “for old times’ sake”.

Yvon came out of retirement for the F750 race at Mosport near Toronto and duly delivered, as he always had, by finishing second to Kawasaki Australia’s rising star, Greg Hansford; both of them ahead of a slew of Yamahas. Yvon then went one better in the 250cc race by winning on the KR250 ‘tandem twin’.

Yvon obviously enjoyed the experience, as a year later he ‘unretired’ himself again for Canada’s biggest race and, with Randy still on the spanners, this time occupied the third spot on the F750 podium.

After that, the popular little French Canadian, who was without doubt one of motorcycle racing’s all-time greats, stayed retired and concentrated upon helping the racing careers of his sons, Mario and Miguel.

Kawasaki, meanwhile, went on to develop the KR250 and its bigger 350cc brother into two of the greatest Grand Prix motorcycles of all time.

And Randy Hall would later be recalled from the development department to form a new Kawasaki US team for a new class of racing that was catching the race fans’ imagination…. Superbikes were Go!