Words: Peter Crawford Photography: Peter Crawford and Mortons Archive

Over fifty years ago, Mike Hailwood stole Triumph’s thunder by winning the Production class at the 33rd Hutchinson 100.

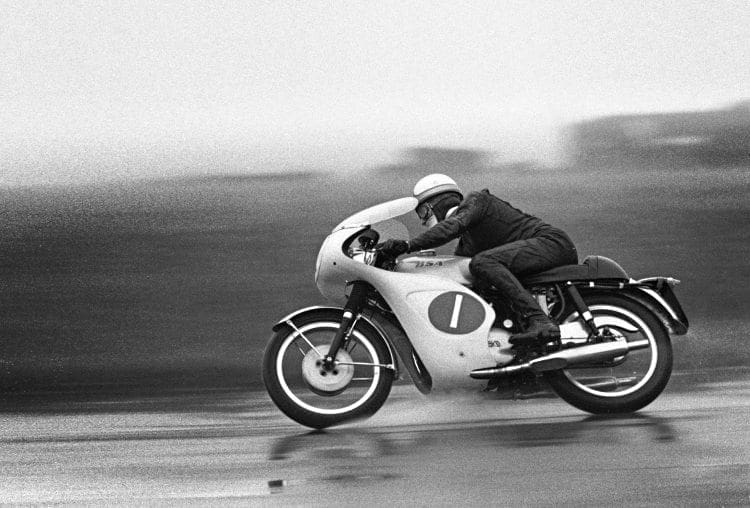

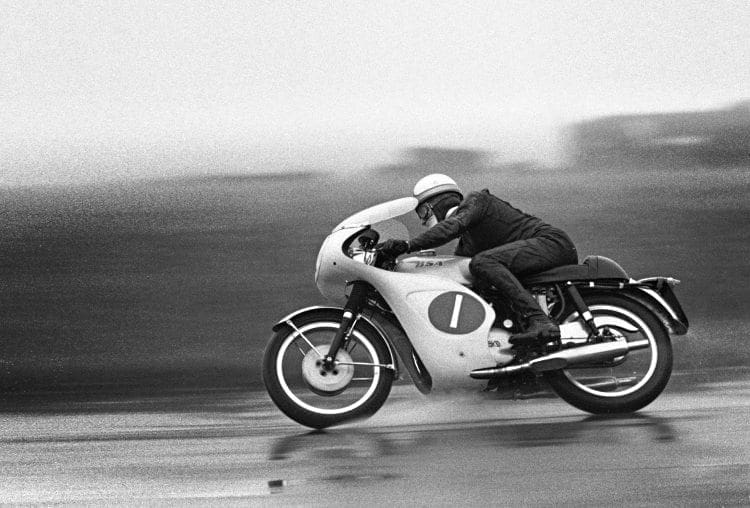

Tip-toeing a Lightning Clubman round a treacherous Silverstone he beat half a grid of Triumphs to record his third victory of the day. Not surprisingly the media proclaimed it ‘Hailwood’s Hutch’. Peter Crawford tells the story.

International meetings waned during the Seventies and were just a memory by the Eighties. A decade earlier it was an entirely different story.

Mallory Park’s Race of the Year, The King of Brands, and Snetterton’s Race of Aces, all commanded as much attention as the national championships, with the Hutchinson 100 arguably pre-eminent.

Embracing both classic and production classes it managed to combine the best of both, attracting impressively international fields throughout the 1960s. It did so largely through a pragmatic approach as the ‘Hutch’ switched classes, circuits and focus over the years.

When established by the Hutchinson Tyre Company, in 1925, it took the form of an endurance handicap event, riders setting off on a 100 mile circuit of Brooklands at intervals based on their bike’s capacities and pedigree.

The fastest man away at the inaugural event started 28 minutes after the first, but as both speeds and the entry improved Les Archer’s Velocette achieved the first 100mph average in 1933. By 1935 Ginger Woods had lapped at more than 115mph on a blown New Imperial.

These were incredible speeds for the time so it was probably for the best that the demise of Brooklands meant a search for both a new venue and format, post-war.

The Hutch settled on Silverstone in 1950 with International status being conferred in 1952.

The ‘100’ title was largely honorary by this point but it had no impact on the Daily Mirror’s decision to sponsor it from 1963 from where on in it benefited from the publicity that only a daily could offer.

The Glorious 33rd

So why mark the 1965 event over any other? Well, it was arguably the Hutchinson 100’s pinnacle and the last year of its 17-year run at Silverstone.

The BMCMC also claimed it the year’s premier one-day event, with race summariser Leslie Nichol going one further, “With six of the world’s reigning champions competing, today’s Hutch may rightly be ranked the greatest one-day club meeting ever held in Britain.”

Ever? Well BEMSEE obviously wasn’t shy in blowing its own trumpet but it was quite probably true. The Champions were Mike Hailwood (500cc), Jim Redman (350cc), Phil Read (250cc), Luigi Taveri (125cc), Kent Anderson (50cc) and Max Deubel (500cc Sidecar), and the supporting cast was no less impressive.

It was the stars who were expected to shine, however, and Hailwood kept to script, by winning his three races.

“Three wins on seven cylinders” was how the weeklies put it. But it wasn’t as easy as it looked. In his final race of the day the MV Agusta made short work of the British singles, as expected.

After overtaking Matchless-mounted, Bill Ivy, he cleared off in to the distance by the seventh of the 20 laps. He lapped only half a second faster than he did in the 350s, but that was a different story.

There was no MV this time, Hailwood relying on a borrowed Tom Kirby 7R. The level playing field meant a closer scrap, with the Nortons of Cooper and Minter able to cling on to the end for a wheel-to-wheel finish.

A mere 3⁄5 of a second separated all three at the line and it was Minter who got the fastest lap, equalling his own 98.48mph record.

But it could have been even closer. Motorcycle Illustrated editor, Cyril Quantrill, commented with a degree of jingoism, which would be uncomfortable today, that the ‘foreign’ machines of Bruce Beale and Phil Read had ‘blown up’, but both Beale (305cc Honda) and Read (254cc Yamaha) had in fact pulled up with rather more mundane mechanical issues.

They had also both led, so had they been able to hang around it could surely have been a different story.

In the other classes Anderson, on a works Suzuki twin, had a far easier time of it, taking the 125s at a bit of a canter.

Honda world champion Taveri was confined to a production twin rather than his four, Anderson’s Suzuki team mate Frank Perris retired mid-race and early leader Hans George Anscheidt had underestimated the conditions, throwing his MZ-Kreidler special away on the first lap, in spectacular style.

That left third Suzuki runner Toshio Fuji to follow Anderson home, though the Japanese rider went one better in the 50s, winning the Milano Trophy for his troubles for the lap which beat an existing lap record by the greatest margin.

The only surprise was in the 250 race, where Mike Duff bettered team mate Read, and where the MZs of Woodman and Cotton of Minter briefly looked like they might rip up the script.

They didn’t.

Woodman frightened those in close proximity by regularly jumping out of fifth while Minter succumbed to a points lead coming adrift.

Peter Inchley’s pursuing Villiers/Bultaco was the next to cry enough with water in the electrics, leaving it to Percy Tait to save European honour, bringing an Enfield GP5 in third ahead of more fancied runners.

Rise of the Proddie Bikes

The domination of foreign, multi-cylinder exotica in the classic classes was expected so fans and organisers looked elsewhere for an upset.

It wasn’t the first time. Echoing the rise of Superbikes in the Eighties, Production racing grew in the Sixties. It wasn’t surprising then that British manufacturers packed the grid, with a line-up that looked more like a Grand Prix.

It embraced 12 different manufacturers and drew much of the attention of the 40,000 spectators.

Press and race organisers similarly concentrated on the proddie bikes, since while a victorious rider wasn’t so easy to predict, the fact he’d be on a British bike was.

It was still patriotic to be partisan, after all, so the programme hardly mentioned Hailwood’s 500cc and 350cc prospects, concentrating instead on his production bike.

“It is a mighty task claiming any world title in sport and an even tougher one retaining it.

Naturally, therefore every challenger in today’s 15-lap production machine race will be striving for the honour of beating ‘Mike the Bike’.

Mike has been nominated by Hornchurch dealer Tom Kirby to ride a 645cc BSA Lightning in this event, for standard production motorcycles, taxed and insured for the road.”

Well, nominated by Tom Kirby perhaps, but bank rolled by the factory. His Lightning wasn’t entirely standard either, being hand built at Small Heath, but in that respect his entry was no different from many others. High street dealers were fronting a number of factory ‘ringers.’

What was Mike Hailwood being paid? When it came to investing in road racing BSA was notoriously short of arm and deep of pocket, but as first prize was only £15 it can be assumed it’d lured him with a bit more than his bus fare home.

Triumph must have dangled a similar figure in front of Phil Read and other factories did similarly.

Nonetheless it was BSA which had invested most, linked to the fact that its new 650cc Lightning had only recently been released.

A version was to feature prominently in the new James Bond movie, Thunderball, and adverts were liberally circulated. The bike was being touted as a foyer attraction in selected cinemas, and the actual Bond bike was to be paraded during the interval, rocket launchers and all.

BSA was obviously hoping for a 007/Hailwood double, but James Bond in this case was actually Chris Vincent, in wax cottons.

“I did a lot of work on Thunderball and had a lot of fun at Pinewood, but time wasn’t on my side. They should have filmed it on the M2, down towards Lydden, as the new bit wasn’t yet open. But it snowed so they had to do it at Silverstone in the end, on Hangar Straight.

“I was in Spain by then but I did the studio and the post-publicity work and had the film crew up with me at Silverstone. So, in the interval I took it out. I still had my Barbour suit on as it was that bloody wet!”

The Deluge

As Vincent pulled off the circuit, riders lined up for the eagerly awaited Production Race.

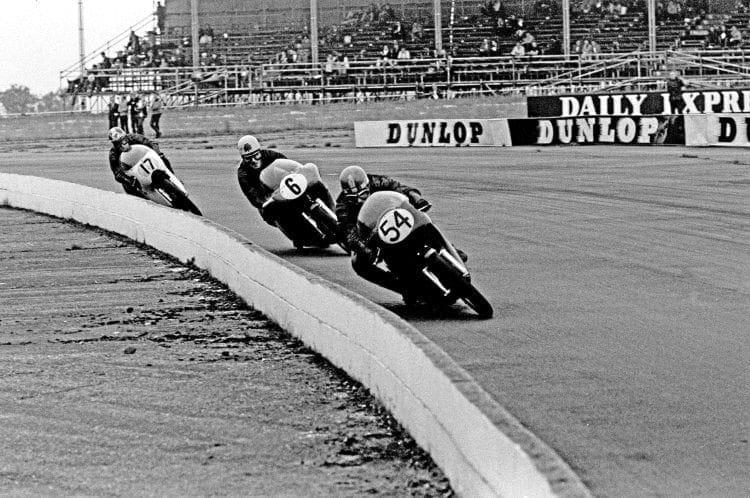

Matchless fielded popular South African, Paddy Driver, and a young Peter Williams, while Norton’s hopes rested on John Cooper.

Triumph had Percy Tait alongside Read, whose Syd Lawton-entered Bonneville had two stable mates, ridden by Syd’s son Barry and Londoner Dave Degens.

The pairing had just won the Thruxton 500-miler, but the event threw a spanner in Triumph’s publicity machine since annoyingly the ‘Thruxton’ had actually been run at Castle Combe in 1965!

Irrespective, Triumphs were pre-eminent and 12 Bonnevilles, more than half the big bike field, lined up.

As such BSA’s second Lightning, entered by Banbury’s Eddie Dow and ridden by Rod Gould, could have been easily overlooked among the Meriden hardware.

The stars didn’t just pepper the biggest-capacity class, however, with the 250s in particular being contested by a range of exotic road bikes you’d rarely see on the high street.

Busiest man of the meeting, Chris Vincent, was probably fortunate his NSU failed to turn up, but Sammy Miller was out on a Bultaco Metralla, Reg Everett on a Yamaha YDS3 and Frank Perris on a Suzuki.

The list went on and on, but unfortunately so did the rain. It always seemed to rain at the ‘Hutch’ and the organisers had perhaps tempted fate; “The change of date from early April to the middle of August will provide, at least, for warmer rain – we hope!”

It poured down and made one novel feature of the race even more challenging. Harking back to a time when the Hutch really was a 100-mile endurance event, machines had to be kicked into life, even though the race was now a 15-lap sprint.

Tait and Miller struggled, but it suited a little-known A J Smith.

He never liked push starts and since he rode a Lightning on the road in all weathers, ‘was able to grab the lead to head Hailwood and the hoard of Triumphs.

Ultimately though ‘Mike the Bike’ did what he was hired to do, dodging the puddles to head Read’s challenge, both with impressive fastest laps of more than 83mph in appalling conditions.

As the weeklies put it; “At the end of the lap Tait had zoomed his Bonneville into third spot behind Tony Smith (Lightning) and Hailwood, with Read fourth.

The pattern soon became plain as Tait, Read and Hailwood pulled away from the rest of the star-studded field. He rode the Tom Kirby 654cc BSA Lightning as if he had been born on it.”

To add to BSA’s joy a 500c Cyclone came third in the 500cc Production class – a placing that was as rare as the 500c version of the Lightning itself – while Gould got fourth in the unlimited.

It could have been better had he and the second works Lightning not temporarily exited the track, at Stowe, on the very first lap. But everyone struggled with the conditions.

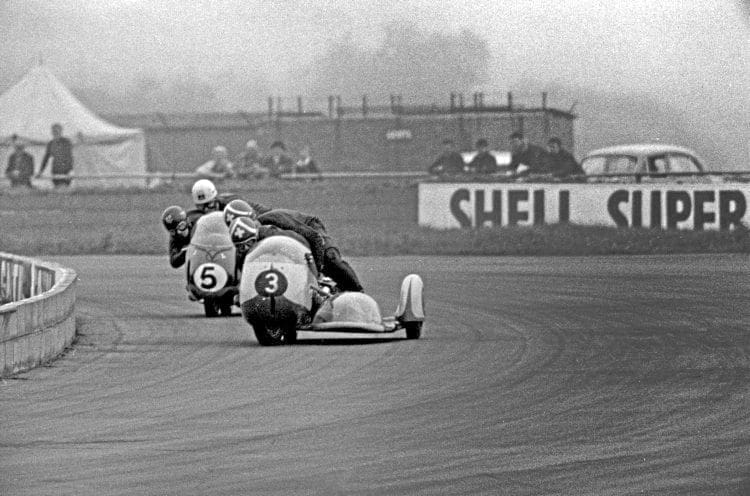

The fans were bedraggled by this stage but BSA smiles grew wider during the afternoon’s 750cc sidecar event, when Chris Vincent drifted his A65-powered outfit to an incredible 45-second victory over the BMW of world champions Scheidegger and Robinson.

That was 45 seconds in just 12 laps! He’d already won the day’s first event, the open race, from a quartet including the 1071cc Mini of Owen Greenwood and GP regulars Camathias, Seeley and Deubel.

That made it three wins out of three for BSA A65-powered machines, but Vincent had little time to celebrate. He hopped directly off the A65 three-wheeler to come second in the 50cc race too, giving good reason to question the ‘Hailwood’s Hutch’ headlines.

The BSA contingent’s smiles were not all for victories either. Unusual at the time, but familiar to current classic race spectators, ex-champions including Geoff Duke, Harold Daniel, Freddie Frith and Bill Doran, on the AJS Porcupine, took to the track during the lunch interval.

Alongside them was ex-Sidecar World Champion Eric Oliver. Looking for a suitable ride and with options oddly thin on the ground, Vincent was quick to offer his own outfit ’if it would fit’.

Oliver was considerably taller than the compact Vincent and more familiar with a ‘sitter’ than the BSA’s cramped kneeler layout. But he took it out regardless. Oliver had been Vincent’s idol so his favourable comments made his day.

He who laughs last

However, the biggest prize of all came several days after the Hutch.

For a man who had ended the day sprawling in the mud; the quick-starting A J Smith. Tony Smith had been campaigning the (genuinely) private Dick Rainbow Motorcycles Lightning Clubman since the beginning of the season.

It won its first race at Brands Hatch in March and Smith had been racking up the victories ever since.

His Lightning Clubman was actually the first ever made. No one gave him much hope at Silverstone, however, and he was barely mentioned in most post-race reports, which was surprising.

He’d led Hailwood; “We went through the season and won virtually everything you could, but when it came to the Hutchinson 100 we figured we had to do something different. So, we did what the factory had done to Hailwood’s bike, which was increase the inlet valve size.

“The problem was we didn’t have the right valve springs so it was actually 1000rpm down on previously. Luckily it rained, which virtually eliminated the deficit and I managed to stay ahead of Hailwood, for a while.

“But it was inevitable and at Chapel curve I aquaplaned off the circuit and on to the grass, stood it up and had to jump off!”

While the A65s of Hailwood, Vincent and Gould were the ones mentioned in the weeklies it was actually Smith’s that was discussed back at Small Heath.

“What I’d done impressed the factory sufficiently for them to give me a call. A month later I was working for the factory. I walked into the experimental department that first morning and asked what to do.

“The foreman said, ‘Build us a race bike’. I was like a kid in a sweet shop. It was the best job in the world! I asked John Hickson, the MD, why he wanted me and he said, ‘Because your bloody bike was beating the factory one!’ I inherited that bike straightaway.

“It was good but in the space of 12 months it was transformed. If Hailwood had the same bike two years later he’d have been even further away!”

But sadly that was the last time Hailwood graced a BSA twin. Smith and Vincent went on to clock up countless victories, both home and abroad, but BSA never again showed the same level of corporate enthusiasm for the racing A65 and never built on the publicity won. It took the Rocket Three to rekindle its interest, but by then the horse had bolted.