Ducati’s Pantah-based V-twins won four World Formula 2 titles in the 1980s. John Nutting tried out the works bikes raced by Tony Rutter in 1984 and charts how they were developed.

Words: John Nutting Photographs: Mortons Archive, John Nutting

When I was invited to try the works Ducatis of the type that had been raced to four consecutive world road-racing championships in the early 1980s, life as a motorcycle journalist didn’t get much better.

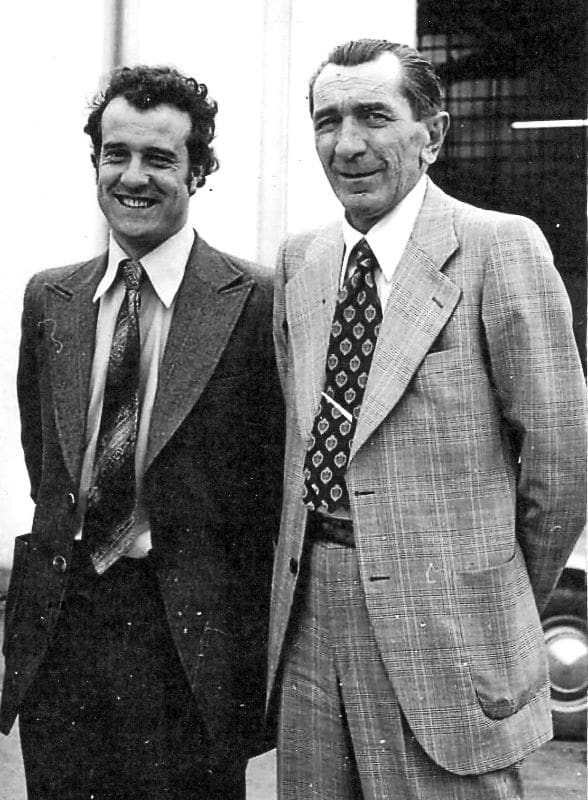

It was towards the end of the 1984 season, and Tony Rutter, who had already clinched his fourth TT Formula 2 title to make it almost his own, was testing the bikes at Brands Hatch. The invitation had come from Dave Burr, manager of Tony Rutter Racing and UK importer of genuine parts from the factory, who was planning the following year to offer for sale Ducatis that would be replicas of Rutter’s title-winning bikes.

He was joined by Pat Slinn, the fabled technician who had been building and preparing Rutter’s bikes since 1981, and who I’d known from his time as the UK Ducati importer’s service manager in the 1970s. His greatest claim to fame had been that he’d helped build the TT Formula 1 world championship-winning NCR900 on which Mike Hailwood had made his famous TT comeback in 1978.

And it wouldn’t be the increasingly common racer test of the time, in which you’d be allowed a couple of laps in company with other journalists: I’d be riding the 600 TT2 and the more recently developed 750cc TT1 version, as they were being prepared for the following weekend’s Powerbike International meeting. I’d have the whole afternoon with the bikes, enabling greater insight into what had created such a successful partnership.

So, with the works Ducatis required to be in peak condition, the pressure was on me not to damage a pair of priceless thoroughbreds.

Rutter’s were examples of what many in classic circles regarded as the last ‘pure’ racing bikes to come out of the Bologna factory. Designed as complete machines by legendary engineer Dr Ing Fabio Taglioni, who retired soon after, they carried a blood line that dried up when the factory turned to liquid-cooled four-valve big bikes for Superbike racing.

The swansong of a career that had spanned the previous three decades, Taglioni’s TT2 machines encapsulated everything that had made his racers so potent, despite having to work with limited budgets.

The TT2 was the racing version of the 583cc Pantah V-twin that was first revealed as a 497cc prototype in 1977. It is estimated – the factory records have been lost, says Slinn – that around 40 of the TT2 machines were produced by Ducati, making original examples very rare machines. No wonder then that over the intervening 30 years a cottage industry has grown to satisfy the need for replica versions.

Taglioni designed the Pantah engine with Ducati’s familiar layout, which he called the L-twin, but it was right up-to-the-minute. Unlike the big V-twins which used a pressed-up crankshaft with roller and ball bearings and a camshaft driven by a shaft with spiral bevel gears, the Pantah used a future-proof architecture that would make manufacture and assembly much more straightforward, and in some ways more cost effective.

This involved the use of a one-piece single-throw crankshaft with plain shell-type main and big-end bearings fed by a high-pressure lubrication system incorporating a replaceable cartridge filter. As well as being less costly and more reliable over higher mileages, this reduced mechanical noise. For the same reasons, the overhead camshafts were driven by toothed belts from a half-speed countershaft between the cylinders.

The engine was remarkably compact despite its air cooling, notably because the cylinders – with a hard Gilnasil coating for the bores, allowing tighter clearances – were deeply spigoted into the vertically-split alloy crankcases, and used oversquare bore and stroke dimensions of 74 x 57.8mm. There were two valves in each head, 37.5mm for the inlet and 33.5mm for the exhaust, opened by a single camshaft, and more importantly also closed by it too, because desmodromic operation was used rather than power-sapping springs, minimising the risk of valve float and enabling, in theory, quicker opening speeds. Enabling the combustion chamber to be more compact, the valve stems had an included angle of 60 degrees, more narrow than the bevel twins.

With a compression ratio of 9.5:1, the first 500cc Pantahs were rated at a modest 52bhp at just over 9000rpm, at the crankshaft. The first racing versions of the Pantah were produced a year after the road bike had been launched in 1979, primarily for domestic Italian championship racing. Two bikes based on the bigger 600SL, launched for 1980, were prepared by racing mechanic Franco Farne using the original frame, and special Marzocchi suspension. Clothed in bodywork similar to that used on the semi-works NCR900 it looked bulky. Power was a healthy 70bhp at 9800rpm.

The emergence of TT Formula racing – as more than a ploy to maintain interest in the Isle of Man as an international racing event – was growing in Europe. The idea of the class was to promote the use of production-based machines, of which 1000 units had to be made in the year before homologation.

Taglioni saw this as an opportunity to put the Bologna factory back on the world’s racing map, and he designed the TT2 based around the 583cc Pantah engine, but with a more compact tubular-steel trellis frame that would become as much a hallmark of future Ducatis as the 90-degree V-twin engine.

With triangulated construction in 25mm-diameter high-tensile steel tubing, the frame made by Ducati’s contractor Verlicchi could be light – just 7.3 kilogrammes – and with four butted mounting points used the engine cases as part of the structure, making it more stiff. Rear suspension retained the swingarm’s pivot point on the back of the gearbox casing but with a single Paoli shock. Up front, a telescopic fork with 35mm stanchions and magnesium sliders was supplied by Marzocchi. Wheels were 18-inch cast-aluminium alloy items from Campagnolo with 2.15 and 3.00 rims. With a 1397mm wheelbase the bike was tiny.

Power was increased by the use of bigger 81mm pistons giving a capacity of 597cc, a higher 10:1 compression, larger-diameter inlet and exhaust valves and higher-lift desmo camshafts with longer opening duration. For the TT2 world championship races the standard 36mm Dellorto carbs were retained. The Italian championships called for the retention of the starter motor and the 200-watt generator. Nonetheless the engine turned out a claimed 76bhp at 10,750rpm, and, with extensive lightweighting of engine parts, all-up weight was still just 123kg.

Taglioni regarded the TT2 as his best design. Before his retirement, he told journalist Alan Cathcart: “It’s the epitome of everything I’ve always aimed for in motorcycle engineering. It has light weight, a wide power-band, slim profile and good fuel consumption. It’s also fast without employing an engine big enough to power an automobile.”

As Ducati’s service manager for the UK market, Pat Slinn says his visits to the factory had revealed these developments but his move to join Steve Wynne at Sports Motor Cycles full time in 1979 enabled him to get more involved with racing. Knowing that the Formula 2 regulations – which had favoured the use of TZ350-powered Yamahas – were likely to be changed in 1981 to limit carburettors to those used on the road bikes, Slinn argued that they should race an F2-based Ducati.

“The new technical specifications would suit the road-based Pantah, and my imagination went into overdrive. The spec allowed for the modification of the valve seats to take larger valves so long as the cylinder head wasn’t machined,” says Slinn. “I persuaded Steve that we should build and enter a bike in the Formula 2 class of the Isle of Man TT. Steve enthusiastically agreed, but we both knew that if we were to be competitive we needed the help of the factory.”

But that help proved to be limited. A meeting during the Cologne Show with Ducati’s commercial director Cosimo Calcagnile and later race chief Franco Farne, resulted in the factory supplying only a very well used 500cc Pantah engine, some high-compression oversized pistons, special camshafts and a racing exhaust system.

“I had asked Ducati if they could supply us with one of the special TT2 frames and suspension that they had been developing and racing in the Italian championships, and the answer was an emphatic no,” says Slinn. “They explained that the priority was to make a batch of these special purpose-built racers for the Formula 2 championships in Italy and Spain.”

But the Ducati people nevertheless saw value in the potential for TT success, and things looked up when Fabio Taglioni invited Slinn to the factory at Bologna, at their expense, to learn about turning the clapped-out test-bed mule he’d been supplied with into a race-winning 600 TT2 engine. In his booklet about the building of the 1981 TTF2 racer, Slinn describes the process in fine detail. Before then, Slinn had committed to finding a rider with TT-winning potential. Tony Rutter, a motorcycle dealer in the West Midlands with two TT wins already under his belt was his tip. Fortunately, Rutter jumped at the opportunity and asked about the bike. Slinn confessed that he was still working on that.

Four months before the 1981 TT, Slinn spent four days at the factory with Guiliano Pedretti, who had built the engine used by Mike Hailwood for his Formula 1 TT win in 1978. Along with the rough 500cc engine that was being shipped to the UK by the factory came two high-compression 81mm-diameter Veglia pistons with a Dykes L-shaped top ring, two special unmarked camshafts, two 39.5mm inlet and two 35.5mm exhaust valves, a pair of highly polished forged steel connecting rods with Vanderwaal big-end shells, and a two-into-one exhaust system. Following his factory tuning masterclass, Slinn brought these back as hand baggage.

In his spare time, Slinn spent more than 90 hours on the engine, which before being worked on had a crack in a mounting boss repaired. Everything that could be lightened and polished, was. The crank and gearbox shafts were precisely shimmed. The pistons were matched for weight and the compression ratio for each cylinder also matched at 10.5:1. The valve rockers were also polished and shot peened for strength. A pair of 36mm Lectron flat-slide carburettors were donated, but a pair of Dellortos we kept in reserve.

Slinn still needed a frame, suspension and wheels. By a coincidence there was a written-off 500SL in the Sports Motor Cycles workshop, so the frame and swingarm were sent to racing chassis specialist Ron Williams of Maxton (with a strong reputation for preparing TT winners and who had most recently been working with the Honda works team on the NR500). “His brief was to convert the frame in whatever way he felt necessary, and supply or modify the suspension and brakes,” says Slinn.

By April 1981, Ron Williams had completed the rolling chassis, which Slinn describes as a “masterpiece” when he saw it. “He had modified the frame, supplied Dymag wheels, Lockheed brake discs and calipers,” says Slinn. “He had modified the Marzocchi front forks, and supplied Koni rear suspension units, the bottom mounts of which had been brought well forward of the standard position, and were almost upright. He had modified the exhaust system for the best possible ground clearance. Ron had supplied everything the chassis needed, including the clip-on handlebars, footrests, brake and clutch levers, brake master cylinders, and even fitted Aeroquip brake hoses and bled the brakes. He had even had the frame and swingarm powder-coated in a very subtle grey/silver colour that certainly gave the appearance of lightness.”

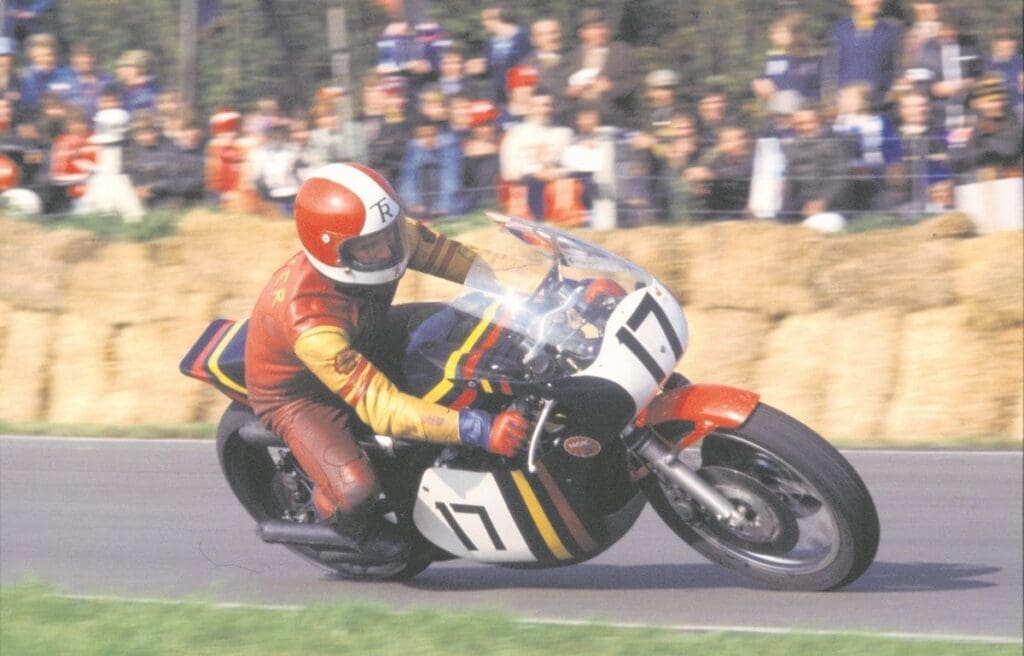

The Pantah SL/TT machine was assembled and following some on-road mileage testing and a session at at Oulton Park the fork leg offset was adjusted by fitting a set of Laverda yokes. After Rutter tested the bike at Aintree he was completely satisfied. In practice for the Isle of Man TT, he broke the TT Formula 2 lap record, despite the bike feeling slower than he expected.

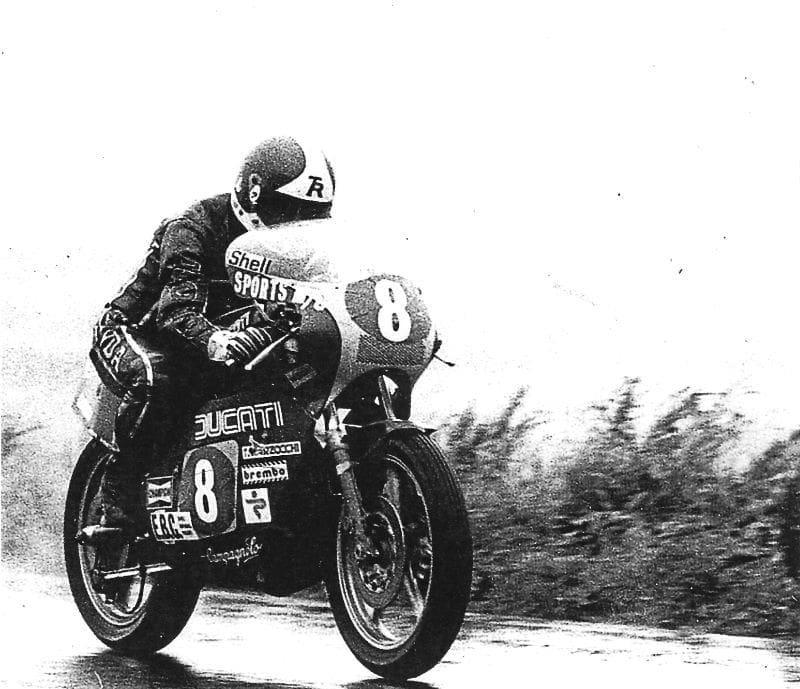

“We knew then that he was a happy TT rider,” says Slinn. Rutter won the TT Formula 2 race with a record 103.5mph lap and was so dominant he was almost two minutes ahead of the second-placed rider, Phil Odlin on a Honda. “Ducati were over the moon and started to promise all kinds of help for the future,” says Slinn. Having realised there was a chance of winning the Formula 2 world title, for the following race at the Ulster Grand Prix Ducati shipped over a factory TT2, which was accompanied by Franco Farne and sales director Franco Valentini.

Conditions in the race were appalling and with heavy rain making visibility so poor that he couldn’t see the pit board markings, Rutter hadn’t realised that Phil Mellor was ahead on his Yamaha. But 2nd was enough to secure Rutter’s first world championship, and Ducati’s second after the epic 1978 TT Formula 1 result with Hailwood.

That particular Ducati was one of the earliest of the factory’s TT2 machines and after the race was returned to Bologna. According to Slinn it came with one of five very special engines featuring magnesium crankcases and a dry clutch. Changes from the original TT2 engine of 1980 included even larger 42mm inlet and 37mm exhaust valves, a camshaft with even longer valve timing (66-96/100-60 rather than 60-90/90-60) and a 10.36:1 compression ratio. Peak power – again about 76bhp – was at about 10,800rpm.

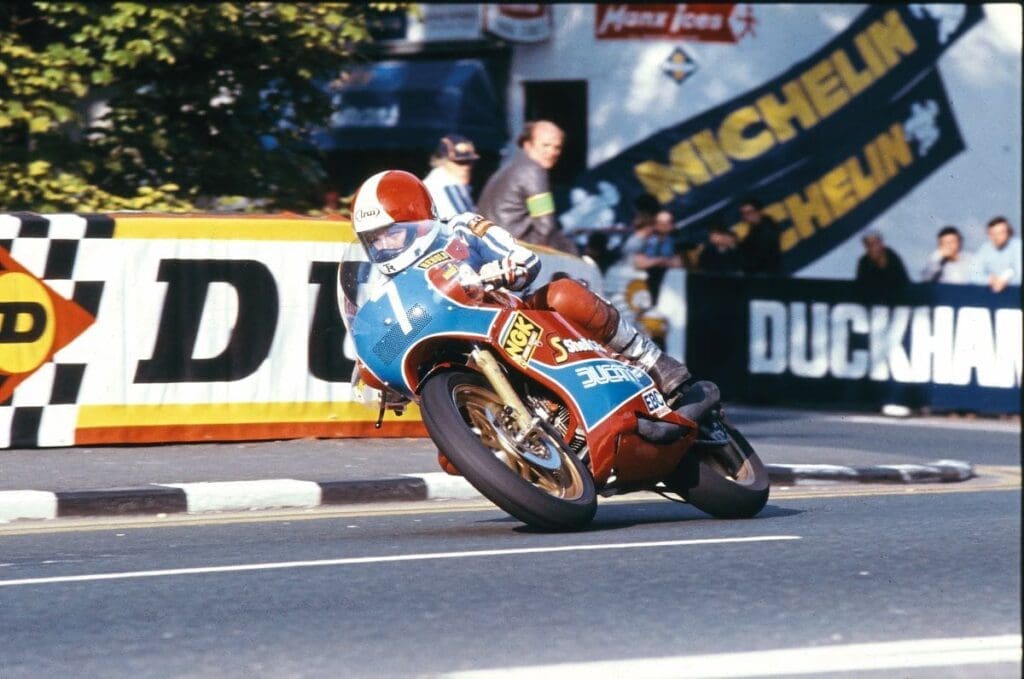

A TT2 with a similar engine was loaned to Tony Rutter for the following two seasons, with the same overwhelming world title success. The victory in the Isle of Man F2 race in 1982 was even more emphatic, with the winning margin at 108.05mph increasing to four minutes over Steve Moynihan’s Yamaha. In 1983, Rutter beat Graeme McGregor’s similar Ducati by 70 seconds to win the TT F2 race. Two 2nd places at Ulster and Assen secured the third title for Rutter.

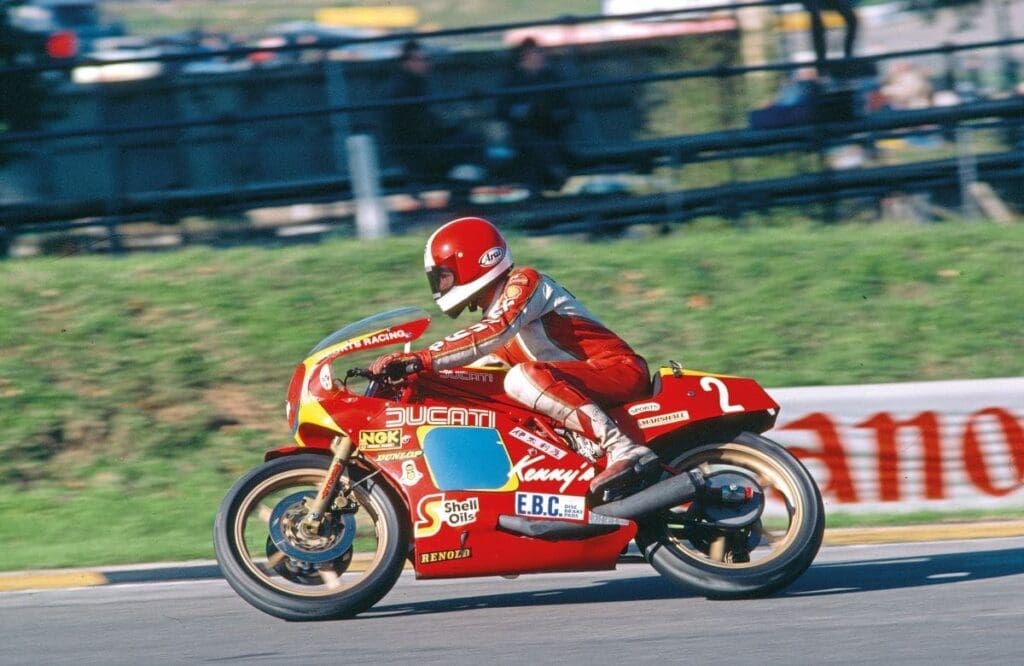

By 1984, Ducati provided a new TT2, along with a new 750cc version for Formula 1 racing, along with spare engines, enabling Rutter to race in a wider range of racing classes such as the Battle of the Twins, just as well because the 350cc F2 Yamahas were becoming increasingly competitive.

Despite coming 2nd to Yamaha-mounted McGregor in the Isle of Man TT F2 race, Rutter won in Portugal, took another 2nd in the Ulster and came 5th in Czechoslovakia with fuelling problems. He still won the TT F2 championship, for a fourth time.

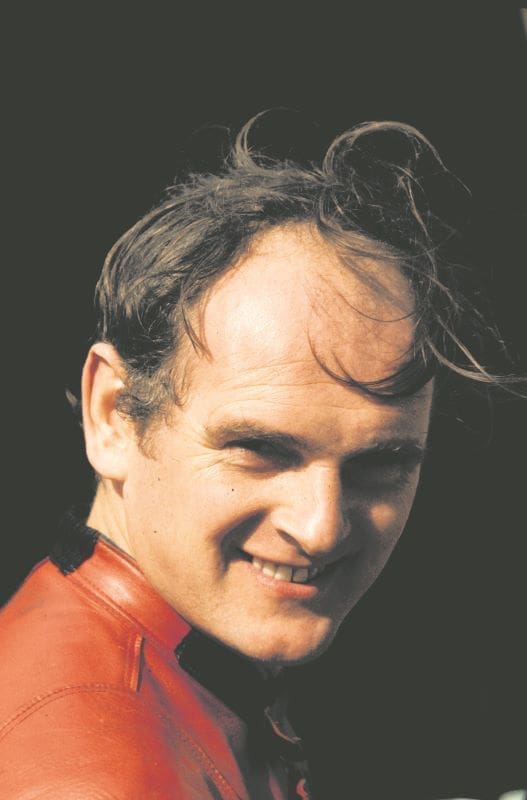

Tony Rutter, the unassuming multi world champion

Supremely stylish but unassuming, Tony Rutter’s 30-year racing career involved machines from 125cc to 1000cc, but his talent flourished best on Yamaha two-stroke twins and Ducati’s V-twins, on which he won seven Isle of Man TT races and four World Formula 2 titles.

Born in 1941, the Brummie started racing at 20, and proved to be adept both on short circuits and the roads, making his TT debut in 1965 and taking his first podium with a second to Giacomo Agostini in 1972. Rutter raced with the John Player Norton team and later with the Honda Britain endurance team on the RCB1000 fours.

Few though could stay with Rutter on Yamaha’s 250cc and 350cc two-stroke twins, on which he also won two British national titles.

He was great on the roads as well, winning nine North West 200 races in Northern Ireland where he clocked the first 110mph lap. His first Isle of Man TT victory was the 1973 Junior which he repeated a year later.

By 1981, Rutter was a seasoned Mountain circuit competitor when he won the Formula 2 TT race on the Sports Motorcycles 600 Ducati, the first of four victories that also came in 1982, 1983 and 1985. Despite coming second in 1984, it still earned him his fourth World Formula 2 title, with the series being also contested in circuits in Europe and Northern Ireland.

The seventh TT trophy was after winning the 350cc class of the 1982 Senior TT. Another memorable TT podium was second on a Suzuki RG500 to Mike Hailwood on a similar machine in the 1979 Senior.

Rutter’s versatility and enthusiasm shone in production racing. In 1975 and 1976 he raced a Mocheck Honda 400 Four and one of his most thrilling victories was during the British Grand Prix at Silverstone in front of a huge crowd in August 1976.

“It’s a beautiful little machine,” said Rutter. “The Honda was going so fast down the Hanger Straight I was passing Kawasaki 900s and bigger Honda fours. I must have been doing close to 130mph,” he gasped as he leant the bike against the pit wall and ran across the track to pick up the winner’s laurels and the impressive Daily Express Trophy.

After recovering from a catastrophic accident in Barcelona in 1985, he returned to compete in the Isle of Man TT until 1991, but was unable to repeat his former glories. Soon after, his son Michael started his own successful racing career on the roads and in British Superbikes, with notable support from Tony over the years.

Following Tony’s death in 2020 his son Michael told MCN: “My dad won the same number of world titles as Foggy did for Ducati. He has been forgotten about a little bit but that’s nobody’s fault other than my dad’s because he just was not bothered about doing any publicity – he was just interested in racing bikes. He kept himself to himself. I’m bad, but he was terrible. You do get forgotten about quickly, but I don’t think my dad minded that, he just enjoyed what he was doing, and I know that he’d be happy seeing this bike going around Brands Hatch.”

An afternoon with the works Ducatis

Although I’d done a bit of club racing in the previous two seasons, even winning a 250cc championship, there’s nothing like being on track with a world champion to bring any rider back to earth.

Both the works bikes were available so Rutter suggested I take the 750 out while he scrubbed in a new rear tyre on the 600. Apart from its engine, the 750 machine was otherwise identical to the 600 and felt tiny, almost like a 250cc racer. Both retained their starter motors but the 750 had a faulty relay, so Slinn gave me a push and I roared after Rutter and out onto the track. The beauty and lasting appeal of the TT2 chassis is that it’s so small and slim and even though you need to fold into its curves it still suits a range of rider sizes. While Rutter was four inches shorter then me, and the bikes were tailored for him, I didn’t feel cramped.

Rutter ambled into the right-hand drop of Paddock and I tucked into his slipstream thinking that if he was taking it easy I’d at least be able get a good view of how such a stylish rider wins races. No such luck. While I thought that the 750 would have the legs of the TT2, Rutter started to ease off into the distance on the smaller bike. Then I realised how he did it, by being naturally fast.

So I contented myself with getting accustomed to the 750. Talk about sublime: the combination of light weight, secure road-holding and flexibility won me over immediately. Booming from the single megaphone, it pulled keenly from 4000 and really started to fly as the needle on the white-faced Veglia rev meter hit 10,000. Rutter said he revved it to 10,500 and was pulling 150mph at the Ulster GP in top gear.

Then I started to worry. Powering out of Clearways, the back end would start to weave and I had to knock it off. Was it me? Luckily Rutter pulled in and trying not to sound too cheeky I asked him what was going on. It turned out that the bike was set up with a softer rear spring for the more bumpy Oulton Park, which was too soft for Brands, and especially with my extra weight.

We switched machines, and although being visually identical, the 600 felt like a completely different bike. On the intermediate patterned tyres – a Dunlop front and Michelin rear – the 600 TT2 was much tauter and the engine crisper: indeed it felt more like the world championship-winning bike I’d expected. It was still remarkably flexible, pulling this time from 6000. I could use just three of the five ratios: down from top for Paddock, down again for Druids, up one for South Bank (or whatever it’s called now), and down again for Clearways where I’d hook up two for the start-finish straight. Rutter said he used four, buzzing the engine harder with a lower gear at Druids to get harder acceleration out of the exit.

Then it got better. Pat Slinn fitted slick tyres to both bikes, and they were again transformed. Suddenly the TT2 felt like I was on a dry road, whereas I’d been on wet before. Soon I could dive into Paddock’s ripples with more confidence and find a smoother line without fear that the back end would let go. Cranked over and powering out of Clearways I could just feel the back tyre on the edge of a drift. Lovely, then Rutter came past looking so relaxed.

For the 1985 season, Rutter and Slinn were hoping to line up lighter works bikes tipping the scales at about 290lb, and with the 600 poking out 81bhp, to keep the Yamahas at bay. But at Barcelona’s Montjuic Park, Rutter crashed the 750, almost destroying it completely, and suffered head injuries that effectively cut short his career as a top flight racer.

Rutter eventually recovered and supported his successful racing son Michael at BSB events, later at classic parades with the 1984 TTF2 championship-winning Ducati and a replica of the F1 750. Rutter died after a short illness in 2020 aged 78.

If ever a stylish rider so well matched a stylish machine it was Rutter and the Ducati TTF2.

Building a Ducati TT2 now

With original Ducati TT2 racing machines being so rare, they fetch huge prices, so it’s no wonder that a market has built up over the years for replica versions, which soon became very popular in the US where they were raced in twins racing. For example, Pat Slinn recalls that an F1 750, a genuine factory bike, sold for $170,000 there, and that was more than 10 years ago.

Harris Performance at Hertford (+44 1992 532500), now controlled by Royal Enfield owner Eicher Motors, was one of the earliest to build replicas of the TT2 in the 1980s. Their frames are made from T45 high tensile tube, bronze welded – not TIG or MIG – so there is less chance of fatigue cracks near the welds. While there was a resurgence in interest in their kits 10 years ago, Harris’s Steve Bayford says there has been less call for the TT2 kits, for which the bare frame costs £2625, but a more comprehensive list of parts can reach in the region of £10,000, even before the engine, wheels, brakes and front fork are sourced.

Andy Molnar at TGA (+44 1772 700700), who bought the Two Wheels Classics business from Jim Blomley a while ago – which included TT2 kits – says that the smaller-capacity classic racing classes “are quiet”. He now finds much less demand for the TT2 replicas – kits for which start at a basic £4200 – than for his Manx Norton kits “which are going crazy”. In the US, Andy’s agent, Scot Wilson at Italian Iron (+1 520 730 7576, www.italianiron.com), is an enthusiastic supporter of TT2 machines.

At the Bologna home of Ducati in Italy, Pierobon (+39 051 405088) also lists the TT2 frame amongst its vintage range. The frames are made from MIG-welded chrome-molybdenum steel tubing using original jigs, the company says.