Unless you were an acknowledged star with a factory contract in your pocket, being a genuine full-time professional motorcycle road racer was no easy task in the 1950s and 60s. Personal or team sponsorship was unknown apart from some support from oil and tyre companies that only went to the top men anyway and, if you were a privateer, as well as the actual racing it usually meant being your own business manager, mechanic, truck driver and travel agent.

Words: Bruce Cox Photographs: Dan Shorey Collection

It meant planning a season campaign that could range from Sweden and Finland in the north, to Spain and Italy in the south and the communist countries behind the Iron Curtain such as East Germany and Czechoslovakia in the east.

The race organisers would pay start money that helped defray travel and living expenses, but offered little in the way of profit unless you got in the top 10 and picked up prize money as well.

And the same was true if you saved on travel costs by staying at home and concentrating on British meetings. Only rarely would a rider get any up-front appearance money from UK track owners. Again, you had to be in the prize money to make it pay.

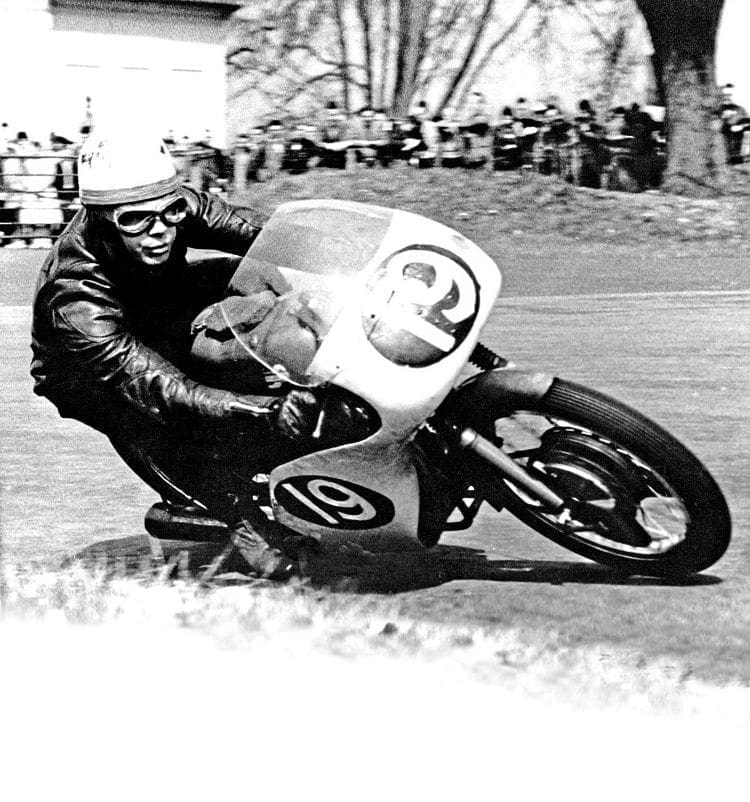

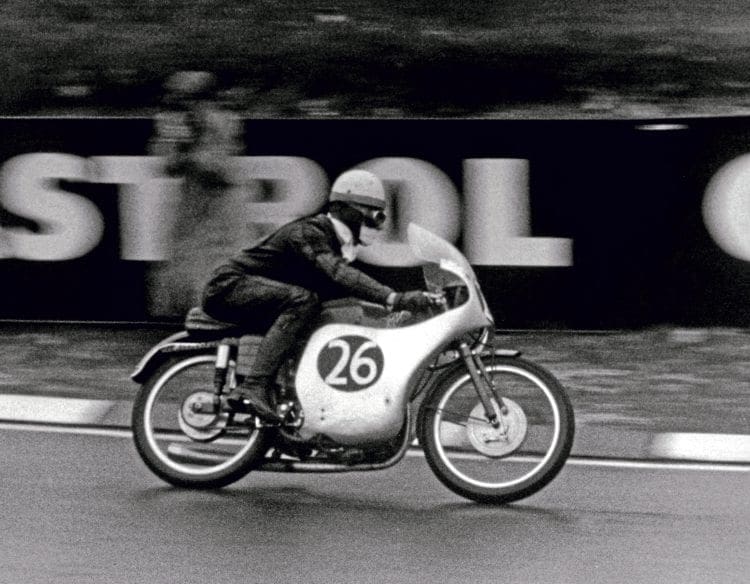

Consistency was the name of the game and one rider who was consistently good over a racing career that spanned 15 seasons was Dan Shorey.

He was the essence of the well-organised privateer rider who went racing in a business-like manner and reaped the rewards of that attitude. He won over 100 races and took more than 300 leaderboard (top six) placings in a road racing career that lasted from 1955 to 1969.

Another key to making racing pay back then was keeping both rider and bike healthy. In all the seasons he spent at racing speed, Dan can count his race crashes on his fingers – of one hand!

He remembers just twice when he slid off on oil and twice more when he was involved in other riders’ crashes (in those he broke first one collarbone and then the other).

Now 77 years old, Dan reflects: “You didn’t make any money sitting on the track or in the hospital. So I aimed to stay on the bike as much as possible!”

Banbury garage owner and Triumph dealer Bert Shorey was a prominent Midlands grass-track rider in the 1930s, so it was no surprise to anyone when his son Dan began racing at 16, wearing his dad’s prewar two-piece leathers and helmet.

From 1954 through 1956 he competed in local scrambles and grass tracks – beginning on a prewar Rudge four-valve 250 with rigid frame and girder forks!

From grass to tarmac

In 1955 he had his first taste of the hard stuff when he rode a Triumph Tiger Cub fast enough to gain a first class award in the Motor Cycling Club (MCC) high-speed trials at Silverstone, which encouraged him to go road racing for real late in the following season.

He finished his first real race in midfield, on a Rudge 250, in what was the second-ever road race held at Mallory Park after its conversion from a grasstrack venue.

By 1958 Dan had gained more road racing experience on the Rudge and had traded it in for the bike on which he really began making his name – the Norvel 250.

This was a Manx Norton fitted with an overhead-camshaft Velocette KTT Mark VIII engine that had been reduced in capacity from 350 to 250cc and, in a period when most two-fifties in British national level racing were based on prewar British bikes, it proved to be a very effective bike indeed.

In the Midlands at the time there were many races on the narrow roads of country estates – just as Donington Park had been when Dan’s father, Bert, raced there in prewar days.

These roads were often so narrow that the events were sometimes referred to as ‘path racing’ rather than road racing!

One of them, at Osmaston Manor, was so narrow that at one point there was even a ‘no passing’ zone where overtaking another competitor meant the black flag and immediate disqualification!

Other such tracks were at Drayton Manor and Alton Towers, now well known as major amusement parks. Back in 1958, Dan raced at Osmaston and on the paths through the rhododendron bushes at Alton Towers to several wins and good placings on the Norvel.

By 1960, Dan had added 350 and 500cc Manx Nortons to his stable of bikes and one of the races he won on a Norton was the Reg Cross Trophy at Cadwell Park.

The race was sponsored by a famous racing clothing manufacturer from nearby Louth and a new set of made-to-measure leathers came along with the prize money.

This was a godsend to Dan, who was still wearing the set of leathers he had acquired in a package deal with the purchase of the Norvel.

And, as he is about 5ft 7ins and probably weighed less than 10st (140lbs) at the time, the fact that the Norvel’s previous rider was a strapping six-footer weighing half as much again meant that they were a less than perfect fit!

But, even though he was working for his dad, Dan was earning just £4 a week and keeping his race bikes going on this and whatever prize money he could win.

This meant there was no way he could afford to re-tailor his leathers. So before each race, he used to pull them up to fit over his legs as best as he could and then fold the spare material around his midriff and hold it in place with a body belt.

This worked well enough while seated on the bike but Dan recalls that after each race he would get off and the crotch of the leathers would be hanging below his knees!

As well as winning the new set of leathers, Dan used some of the prize money from the Cadwell win to have Reg Cross tailor his old ones to fit which, quite possibly, made him the only young rider in England to have two sets of tailor-made leathers!

The Shorey family’s North Bar Garage in Banbury was also the local Triumph dealer so in 1958 Dan had gone to the factory at Meriden on a six-month apprentice course to learn the ins and outs of building the company’s little single-cylinder 150 and 200cc engines and the big 500 and 650cc twins.

Thus was earned a skill that stood him in good stead throughout his racing career. He never regarded himself as a ‘tuner’ so his race engines went first to Bill Stuart and then, later in the 1960s, to Ray Petty… who were both very well-known as tuners of Manx Nortons.

But Dan maintained the bikes day to day throughout the season and breakages were rare indeed.

His careful maintenance paid big dividends, especially as racing on the Continent, far from his base in Banbury, meant that bikes had to get off the line to be able to earn the start money appearance fees – and then they had to get past the chequered flag in order to win the prize money.

First big win

In 1958, when Dan was 20 years old and on the Triumph apprentice’s course, there was an 18-year-old kid by the name of Mike Hailwood working on an adjacent bench at Meriden.

With Dan’s dad having the Triumph agency for the Banbury area and Stan Hailwood’s massive Kings of Oxford dealership also selling Triumphs by the shedload, it was almost inevitable that the two boys would team up on a 650cc Triumph Tiger 110 for the Thruxton 500-Mile production bike race on the old airfield circuit down in Hampshire.

In terms of preparation, Dan was able to give Kings of Oxford mechanic John Dadley a few tips on securing the things the big-twin vibrations used to shake loose – in particular magneto screws and rocker box adjuster covers.

Otherwise all that was needed was a ‘plug chop’ pre-race, after which inspection of the spark plugs revealed that one of the cylinders was running a little weak and the other a little rich.

Dan recalls: “We went up slightly on the jetting for the single carburettor so that both cylinders ran a bit on the rich side and then it never missed a beat for the 500 miles.” The pair of young Oxfordshire ‘up and comers’ won the race at an average of 66mph.

And Dan’s association with Mike Hailwood continued into the 1959 season, for which he acquired the single overhead-camshaft MV Agusta with which Mike had pretty much dominated the 125cc class in 1958. Mike had moved on to a Ducati for 1959. “Which meant that I got a lot of second places that season!” Dan remembers.

By 1959, despite the presence of Mike Hailwood, Dan was very definitely one of the fastest young ‘up and comers’ in British racing – so much so that he was awarded the Pinhard Prize at the beginning of that year, which honoured him as the best UK motorcycle rider under the age of 21.

The prize is still awarded each year by the Sunbeam MCC in honour of its founder in 1924, Fred Pinhard, who remained as secretary until his death in 1948.

It is still a big honour for young British riders and road race fans will certainly recognise the 2008 and 2009 winners, MotoGP racers Scott Redding and Bradley Smith. And previous names on the trophy include World Champions John Surtees, Mike Hailwood and motocross champion, Jeff Smith.

In 1960, Dan acquired Mike’s Ducati – the bike he had chased throughout 1959. But he ruefully recalls: “It was so much faster than the MV but nothing changed for me as Mike had got the Ducati works ride and the new desmodromic valve version of the 125cc engine. So I still got lots of second places!“

Like Mike, Dan thought nothing of riding four classes a day – or even five when the little Tiger Cub had an occasional outing if there was a 200cc race.

And switching between the Cub and big bikes like his Nortons, or even the Norvel, meant that he had no problem doing the same when he got the little MV 125 and made a serious move into the smallest class.

There was another change of machine for Dan in 1960 as there were more German and Italian machines appearing in the 250cc class of UK national racing – notably the German NSU Sportmax that had first been successfully used in British racing by John Surtees and Sammy Miller, and then by Hailwood.

The faithful Norvel was easily outpaced by bikes like this, so Dan retired it in favour of his own NSU and was soon one of the front-runners in the 250cc class again.

That year, he was also back at Thruxton for the 500-Miler with a new Triumph Bonneville entered by the family’s North Bar Garage. He was partnered by Ginger Payne and the pair finished second to Ron Langston and Doug Chapman on their 650cc AJS 31CSR Sportstwin.

Dan and Ron, who lived about 30 miles west of Banbury near Chipping Campden, became good friends, especially after Ron had begun riding in trials with an Ariel 500 sidecar outfit in 1960 to “have some fun in the winter and to keep fit”.

Ron being one of the best all-rounders in the history of the sport, it naturally got more serious than that.

After quitting his short but spectacular road race career at the end of the 1962 season, he went on to become five-time British Sidecar Trials Champion.

Dan had a similar outfit with which he too enjoyed himself in the winter time and kept fit for the following road race season.

So, in the mid-60s, he and Ron would often be seen blasting around the countryside together in Midlands and National sidecar trials – and each had plenty of respect for the other’s skills.

In the Points

Throughout the 1960 season Dan enjoyed a lot of success with the ex-Hailwood Ducati in the 125cc class, despite never being able to best Mike on the factory desmo model.

The little Italian four-strokes were the class of the field but he and the other front-runners in the 125cc class had begun to notice the speed and good handling of a neat and simple two-stroke from Spain by the name of Bultaco.

Ken Martin was its rider but he had made the mistake of entering for two different events on the same day, for which the ACU administered the draconian punishment of suspension for the entire 1961 season.

John Anelay, the British importer of the bikes, needed a rider and Dan, usually only ever beaten by Hailwood in the 125cc class, got the call.

“I jumped at the chance to be able to ride a bike that I didn’t have to pay for,” says Dan. “Remember that I was only earning four quid a week and trying to buy four competitive racing bikes and keep them going on what prize money I could earn wasn’t easy”.

So off he went to the Bultaco factory in Barcelona to pick up the bike ready for the 1961 season and also took the chance to contest his first overseas race – the Spanish Grand Prix.

This took place right in the centre of Barcelona on the city’s infamous Montjuic Park circuit that wound up and around the prominent hill on which stood the imposingly domed Palace of Fine Arts.

It was a mixture of fast flowing corners up the hill followed by a series of hairpins and right-angle corners on the steep descent back to the start.

Unfortunately, the home-grown Bultaco 125 had trouble but Dan finished a fine sixth on the NSU in the 250cc class to earn a World Championship point on his GP debut.

As well as racing at Montjuic when picking up the Bultacos, Dan also raced on the city park circuit at Zaragoza in north-western Spain when returning the bikes to the factory in October and took his Nortons along as well.

He did so well on the cobblestone roads of the Zaragoza Park that he actually continued going back each year, even after he had finished riding the Bultacos.

He rode there for six years and always finished second or third. As one of the circuit stars, he could always command good enough start money to make the return visit worthwhile in the following season.

Dan recalls: “There always seemed to be sand on the park roads. I never used to start going fast in practice until the sidecars had been out and cleared the track surface for us. Once they had cleaned the sand out of the cobblestones you could really start to press on!”

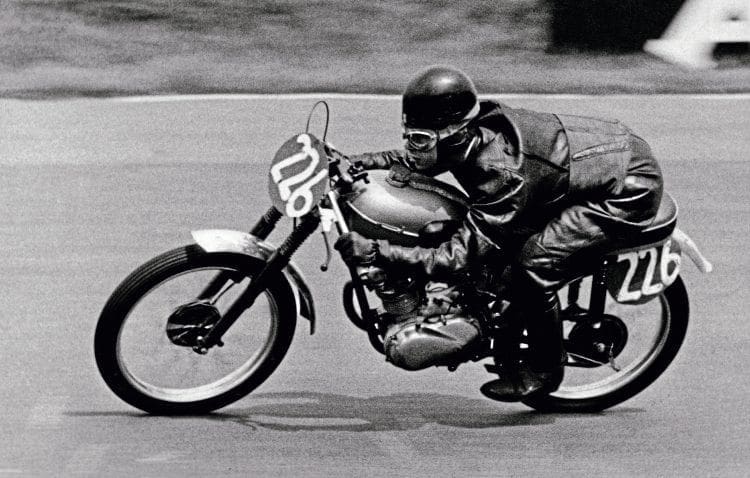

Back in England for the 1961 season the little Bultaco two-stroke was a sensation.

Dan used it to score numerous wins, places and fastest laps and, as a result, was awarded the ACU Star (then the equivalent to a season-long British Championship) in the 125cc class.

By now he was one of the fastest and most versatile riders in Britain, as evidenced by the fact that he set the lap record in all four classes – 125, 250, 350 and 500cc – at the demanding and dangerous little circuit at Aberdare Park in South Wales.

That was also the year in which he contested his first Isle of Man TT, having ridden in the Manx Grand Prix since 1958, with a best MGP position of ninth in the 1960 Senior race at 89.81mph on his 500cc Manx Norton.

So a good measure of the speed of the little Bultaco was that Dan finished ninth in the 125cc TT and topped the 80mph mark with an 81.79mph average speed.

In the 250cc race he placed eighth on the NSU at 84.28mph, which helped alleviate the disappointment of two DNFs for his Nortons in the bigger classes.

Dan rode in the Isle of Man until 1967 but it was never a truly happy hunting ground for him, particularly in the bigger classes.

The faithful Bultacos gave him better results and in 1962 he placed sixth at 82.59mph in the 250cc race on the new 196cc version of the bike.

The sturdy little Spanish bikes were ultra-reliable, with much credit for that also being due to Dan’s meticulous preparation.

All that they needed in terms of spares were one piston and one big-end bearing each over the course of an entire season.

They helped make 1962 a very good year indeed for him. He won the ACU Stars in both 125 and 250cc classes with the Bultacos but it was sadly his last season with the Spanish marque as the UK importer was changed for 1963 to a company more interested in motocross and trials.

Mention of trials brings a little known fact to mind. The first ever Bultaco trials bike seen in England, or anywhere else for that matter, was the one that Dan rode during the winters of 1961 and 1962.

He had been provided with a 155cc trail bike by the factory and converted it to a workmanlike little trials machine by changing things like handlebars and footrest positions.

It was a good enough machine – and Dan was a good enough trials rider – for him to win a sizeable number of First Class Awards in local Midland and South Midland Centre trials.

Later on, of course, Sammy Miller was employed by Bultaco to design and build the Sherpa T… one of the best trials bikes ever. But it was Dan’s efforts on the little converted trail bike that convinced the factory that trials competition was a worthwhile market to provide a proper bike for.

In 1962, an unexpected and last-minute chance of an extra TT ride also added a unique name to the list of bikes raced by Dan during his career. In the middle of the week of TT practice he was offered the chance to ride the works 50cc Kreidler and jumped at it, even though there was only the one lap of practice on the 37¾-mile Mountain Circuit before the race itself.

And even during the first lap of the race he was still getting used to the unique 12-speed double gearbox of the little jewel of the German engineering art.

This had four speeds changed by foot and then had those gears multiplied by a three-speed additional overdrive box shifted by a twist grip on the left handlebar.

Dan recalls that he was never really sure which gear he was in but just concentrated on ringing the changes and watching the rev-counter to make sure that the needle stayed in the five-figure rev-band where the maximum power was delivered.

The result was a praiseworthy 11th place at 69.83mph in a race that included four factory Suzukis, four factory Hondas and four factory Kreidlers! For the record, the race was won by Ernst Degner on a Suzuki with Luigi Taveri and Tommy Robb second and third on Hondas.

Fourth was Germany’s Kreidler team leader Hans-Georg Anscheidt, with Dutchman Jan Huberts in seventh, Dan was 11th and his other German team-mate, Wilhelm Gedlich, finished just behind him in 12th to complete the team effort. Every one of this top dozen was on a full works bike.

As a result of getting to grips so quickly with the very different riding technique needed to extract the maximum performance from the little 50, Dan was signed to the Kreidler team for the rest of that season.

He scored a ninth place in the team’s home West German GP at Solitude and a sixth across the border at the Sachsenring in East Germany.

That was his best result and earned him his single World Championship point in the class. It was a hard-fought point in a class always stuffed with the latest factory race bikes from Suzuki and Honda, let alone his team-mates at Kreidler.

Full-time job

With no Bultacos from 1963 onwards, Dan stopped riding in all four classes that season and concentrated on the 350 and 500cc categories. And, as he always had done, he continued to go racing in a very business-like manner.

“It was my full-time job,” he says, “so I had to take the season planning as seriously as I did the actual racing and make sure I entered for races in which I knew that I could finish in the money. Thankfully, I was a capable rider on any track, whether a wide-open old airfield like Silverstone or Snetterton or tighter road-type circuits like Scarborough or Oulton Park”.

Looking back, he says: “I liked some more than others, of course. For example, I knew that I could always earn a shilling at Cadwell Park!”

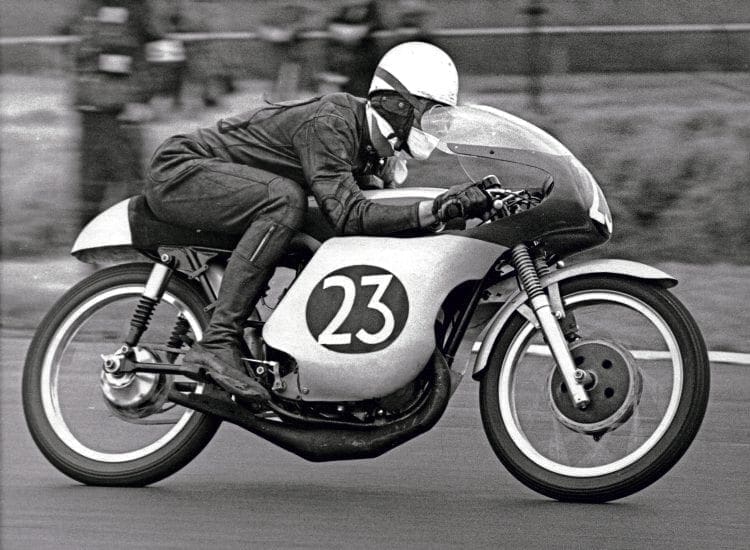

Dan was aided in earning a shilling or two in 1963 by getting the ride on Tom Arter’s AJS 7R and Matchless G50 racers that were essentially factory bikes provided to Tom by the marques’ parent company Associated Motor Cycles.

His most memorable ride on the Arter bikes came on the 7R in the 350cc Italian Grand Prix at Monza at the end of the season.

For some reason the bike refused to start until he had pushed it for about 100 yards, after which it fired up when the rest of the field were almost out of sight.

In an inspired charge through the pack, he finished fifth, gaining two championship points and the honour of being the first privateer home behind the factory Hondas and MV Agustas.

Other high points of the season on the Arter Ajay were setting a new 350cc lap record at Scarborough and winning the 350cc race at the Mallory Park Post TT International by a good margin while riding an untried spare bike.

This had been hurriedly unloaded from Tom’s van and quickly made race-ready after Dan’s number one machine had given him a heart-stopping moment in practice by breaking a con-rod coming out of the Devil’s Elbow.

After the 1963 season Dan reverted to his own Manx Nortons and from then on he had his engines prepared by Ray Petty – another of the era’s leading tuners of big British singles.

From then on, until he retired in 1969, Dan could be relied upon to be in with a chance of a solid top 10 spot in any of the Grands Prix that he contested, often in one of the top six leader board places.

Amongst his best efforts was a sixth in the 1965 Dutch GP at Assen, followed up by a fourth there two years later.

The longer public roads circuits like the Sachsenring in East Germany and Brno in Czechoslovakia were also amongst his favourites, as evidenced by a sixth in Germany in 1967, sixth in Czechoslovakia in 1968 and fifth there in his final GP in 1969 – this time on a Seeley G50 Matchless.

By far Dan’s best Grand Prix result, however, came in 1968 at the Nurburgring when, on one of his faithful Nortons, he finished second to Giacomo Agostini and the mighty 500cc MV Agusta, with Peter Williams on the Arter Matchless third.

And this was no flash in the pan. Earlier in the year he had also finished second to Ago at Mallory Park, lapping only half a second slower, and had hounded the multiple World Champion so hard at an end-of-season Brands Hatch meeting that the Italian superstar slid off at Paddock Bend.

Dan recalls: “Derek Minter and I were so close behind him that I actually saw daylight under his rear tyre at the point that he lost traction. Afterwards he told me that we were just pushing him too hard and he overdid it.

“After Ago was out, I had a great battle with Minter that went down to the last lap. I held him off until he passed me again halfway round but then I got a better drive out of the last corner and beat him by half a wheel”.

Being a full-time professional back in the 1960s meant careful and continuous maintenance of the bikes and a common sense attitude to picking and choosing the race meetings at which you rode them.

Therefore, Dan was quite happy to pass up on a long trek to a Grand Prix in Sweden or Finland in favour of a UK race meeting at tracks like Brands Hatch, Mallory Park or Cadwell, where he was, by that time, earning appearance money and was also confident of getting into the prize money, barring accidents or mechanical misfortunes.

Even so, nobody was getting rich, whether at home or on the Continent. A good example of what the Continental Circus riders had to do to maximise their income back then was provided by Dan in 1966 when, after finishing in second place in a race at Salzburg on the Saturday, he then drove overnight from Austria right across Germany to a race at St. Wendell, 400 miles away in the Saarland close to the French border.

After very little sleep he managed to finish fourth there to pick up some extra cash on the way back to England.

The old Salzburg circuit was a public roads circuit and was used for the Austrian Grand Prix in the days before it became a World Championship event and the new Salzburgring circuit was built.

It was one of Dan’s favourites and he scored the Austrian GP win there in 1965, as well as that second place in 1966.

One leg of the lap was a blast down a stretch of autobahn but that was followed by a hairpin into a cobbled section that crossed over the main straight and went through a series of corners before a chicane and another hairpin led back on to the motorway again.

Says Dan: “I don’t know why but those particular cobblestones had plenty of grip. You could really grind the footrests away”.

And that was the mark of the professional rider in those days. You had to be prepared to grind away the footrests on cobblestone streets as well as on the smooth surfaces of the purpose-built short circuits.

Dan Shorey could cope with them all and, both in his racing and his attitude to it, was one of the most professional of the full-time privateers of his day.

Read more News and Features online at www.classicracer.com and in the latest issue of Classic Racer – on sale now!