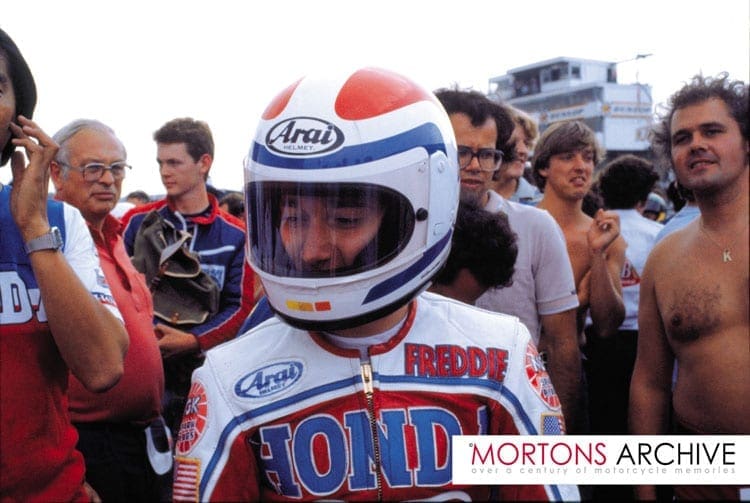

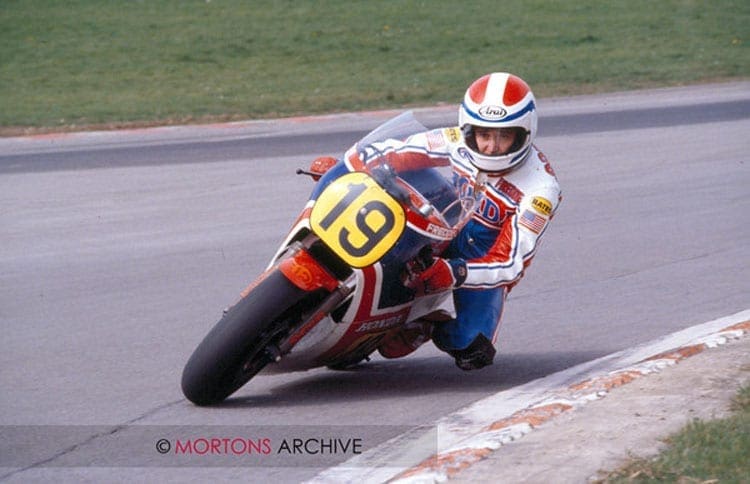

After Freddie Spencer won his first 500cc title in 1983 at 21, making him the youngest person to do so, Honda created the radical NSR500 V4 for the following year.

Teething problems and a broken collarbone relegated him to fourth in the championship, despite three race wins. Here’s Fast Freddie’s talking about his road to the 1985 championship double:

During that 1983 season, it became clear we were limited on how much further Honda could take the three-cylinder. We’d suspected that the Yamaha would be strong. When Barry Sheene got on it and had them put the engine further back that’s what immediately made it handle better.

Unfortunately he got hurt at Silverstone; he would have been tough to beat if that hadn’t happened. As the season went on it became obvious Yamaha was catching up on handling, and already had the engine performance advantage. I heard a little bit about a possibility that there was a (Honda) four in the works. After we won the 500 championship I went to Japan and raced in the All-Japan GP at Suzuka, and won that.

On Monday I heard there was a chance that we were going to see this V4. I was pretty much in disbelief; the fuel tank under the motor, the exhausts over the top of it. Really? OK, that’s fine; Honda knows what it’s doing.

“I was pretty much in disbelief; the fuel tank under the motor, the exhausts over the top of it. Really?”

The first time I rode the bike it didn’t really feel much different in handling than a conventional one. I had my attention elsewhere, the main thing I was really focused on was the engine, and I immediately noticed that the power delivery was so much different from the three-cylinder.

On the three the initial pickup was a lot better. But the new V4 took time to get going. However, as soon as the engine picked up, it really, REALLY motored. The characteristics of the three-cylinder motor were almost like a motocross engine, because Miyakoshi-san, who designed it, was used to working on dirtbike motors.

The success of the three-cylinder meant he was put in charge of designing the V4; it was like a thank you for building Honda’s first 500cc World Championship winning motor. The philosophy behind it was the belief that you had to get the centre of gravity way, way low.

So the bike was very flat, but with a very steep steering head angle, which caused problems with wheel clearance under braking, and radiator size. I usually find the weaknesses in a new bike pretty quickly, so my initial feeling was not so bad. The strength of this design was supposed to be high-speed stability, and through the Esses it felt pretty good.

The initial feeling with the three-cylinder was very responsive, after that it would go flat and then pick up again, but on the V4 it was a little less responsive initially, but then it was more linear in delivery.

The next issue that came into play was ground clearance and this was also the first time that I’d ever run a radial tyre on the rear. It wasn’t till we got to Australia in December and tested for the first time at Surfers Paradise that we found the extra grip meant more lean angle, so now we gotta narrow this thing.

The only way to do that was by making the bottom part narrower, which meant pushing everything else further up as there was now less room to stop the fuel moving around. Our first race was in the Daytona 200, and it felt pretty good there. But Daytona doesn’t really stress anything in the handling department too much. Daytona was the first place we had an exhaust problem – it split after my second fuel stop.

After the Daytona race I had a talk with Jean Hérissé of Michelin and I told him there was something wrong with the tyre he’d put on at that fuel stop – but we checked it, and there wasn’t anything wrong with it. But I had felt it, absolutely. So, then we go to South Africa for the first 500GP race; I go out, do a quick time, put on another wheel, go another half a lap – and something exploded. The last thing I remember is lining up to pass Barry on his Suzuki, and the next thing I know I’m looking at the hay bales.

I get back to the pits and my feet are broken, and so is the wheel. Erv Kanemoto comes up, and he’s just pale as a sheet. He says, “You know, that was the wheel we put on at the second fuel stop at Daytona”.

And I’d felt there that something wasn’t right, but kept on running, finished the race second to Kenny because of the split exhaust – and it’s exploded half a lap later 12,000 miles away. Even now I get a shiver thinking of maybe having that crash on the banking at Daytona.

That injury put me out of action for Spain, but then I came back for the Italian GP at Misano, which I won on my comeback. Honda had done nothing with the bike in the meantime except put metal wheels on it. Then we go to Donington for the Transatlantic Match Races, and with a couple of laps to go I went in a turn just like I had all along, and probably the fuel moved around in a near-empty tank, and I tuck the front end and crash.

But the first indicator we were having some trouble was when we were in Salzburg, high up in the Alps, and we couldn’t get that thing to run fast no matter we did.

‘I appreciate that, but don’t do it again’

At Salzburgring it wouldn’t even pull sixth gear, soon the last lap Randy Mamola pulls over and lets me through to get second. But I told him on the podium, I appreciate that, but don’t do it again. I was getting really grouchy about things. We had a fuel pump inside the tank, and the fuel pump was pumping air because they didn’t have the tank baffled properly. So we go to Germany, and on Friday after the practice session I told Mr Kanazawa and Mr Oguma that I wanted to ride the three-cylinder again.

All the advantages it was designed to display weren’t coming out, plus working on the thing was a problem which cost us the Dutch GP. The plug cap came off and George Vukmanovich couldn’t push his hand through the exhausts to get at it – he was getting second-degree burns trying to fix it.

“I broke my collarbone at Silverstone, so I was out for the rest of the year, and the championship was over.”

So, now we’re in Germany at Hockenheim, and I told Kanazawa and Erv I wanted my three-cylinder back that I’d given to Randy. Turned out the only choice we had was to get Marco Lucchinelli’s ’83 chassis that was on display in the Honda lobby in Belgium, and so they went there and got it.

The ’84 three-cylinder engine wouldn’t fit the ’83 chassis, but somehow they built the bike up in time for practice the next day. Kanazawa said he knew if they could build the thing that in the end I’d do whatever I needed to win with it – and I did indeed end up winning the German GP.

Then they fly over an improved V4, and so I race that in France andYugoslavia, and I win both times. For Assen I wanted to use the three-cylinder, but Yamaha must have had its lawyers checking the small print and found something in the regulations which frightened Honda enough to make me ride the V4.

For Belgium the next weekend everything was straightened out, and I switched back to the three-cylinder and averaged more than 100mph to win. Then I broke my collarbone at Silverstone, so I was out for the rest of the year, and the championship was over.

New dawn

Honda always worked on the principle that this year’s bike had to be better than last year’s. We all decided we’re going back to super-conventional for next year and the 250 we’d decided to build showed us how to do that.

Honda already had a production 250 that wasn’t really up to much – trying to get a slice of the Yamaha TZ250 market, and it wasn’t really a very good attempt.

I remember very clearly the moment that all changed. I was coming into the pits after the problem at Assen – and everything leading up to this event influenced everything that happened from this moment forward.

Everything about the whole year came into that focus at that moment. So we’re all in the motorhome afterwards, and I say – guys, we’re not going to win the World Championship this year, so let’s make up for it by winning two next year.

The last time I’d ridden a 250 was in March 1980 at Daytona, and I didn’t win that race Tony Mang did. My last full season of riding a 250 was in the AMA Championship with Erv when I was 17 years old. Mr Horike got a clean sheet of paper to design the 250. He was a young engineer, and the only thing he’d done before that was to design the carbon-fibre wheel I crashed on at Kyalami.

What he did then more than made up for that, because in three months he took that 250 from an idea to the NSR250 I tested at Suzuka in September, which was by far the greatest bike I would ever race.

What had to happen to get Mr Horike in a position to design the NSR250 is what really made the NSR500, which has since gone on to become the most successful Grand Prix bike.

So I’m riding that 250, and right away I just loved this thing; I’m going quicker than a 250 has ever been around Suzuka before. But then it rained a little bit, I’m coming into a downhill right turn and I hit a wet spot. I tucked the front and think I’m down – but that 250 goes, ‘No, we’re not crashing!’ and it just picks itself right back up, and resumes normal service.

I said to myself, ‘It’s the motorcycle that saved me, it wasn’t me.’ That bike was great from the very beginning; it was completely different from any other Honda GP bike I’ve ever ridden, different from the three-cylinder and definitely different to the V4.

The difference was in the 250’s overall feel, its overall friendliness – it was so well balanced. I always wanted to race bikes that had this forgivingness factor. I always believed our goal was to push, push, push, push beyond what was possible, and then the bike tells you – oops, hey, that’s enough, and that’s when you’ve got. It was one of the most seminal moments I have ever experienced on a motorcycle. I said, OK, this is the starting point for the 500 – let’s make a doubled-up version.

Even so we went to Australia in December with the old upside-down ‘84 V4 still trying to figure out if putting weight at the top would fix it.

I never saw the conventional NSR500 until Daytona; I never tested it anywhere. Plus we were having some serious issues on the 1984 500 with Michelin’s front radial tyre. On the 250 the radial worked fine, but that was because the bike was designed around it, whereas the 500 had been made for a bias-ply tyre.

My first race with the NSR250 was at Daytona, and I won that – and then we went to South Africa for the first GP, and I won again there on it. It was without question one of the easiest bikes ever to race, so well balanced and forgiving, and you could ride the thing so hard.

That hurt us as the season went on, Honda stopped working on it, because the NSR500 was the problem. There was another thing that the 250 steering input. But the 250 when Horike designed it, you knew it had something; so now, let’s try to bring that to the V4.

In testing they were running into some issues with the radial tyres, with chatter all the time. The 250 suffered from that a little, but not nearly as dramatically.

There’s more in the original article – from Classic Racer May 2015.